Rock is remarkable stuff. It lets you know when it’s not happy, and like the best of us, it gets stressed from time to time. When it gets very wound up, it won’t shut up until something finally happens to calm it down, which is usually not a good thing for us humans. Ask San Francisco.

I’m Stressed. Go Away.

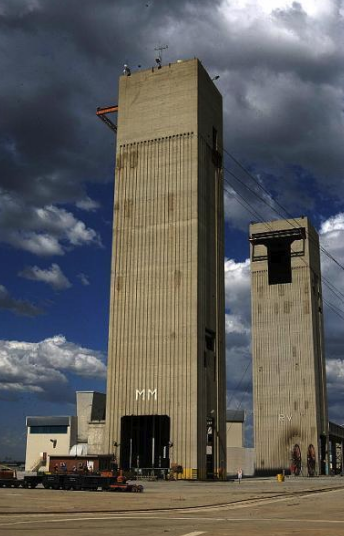

The rock was yapping away to itself late last year in northwest England, at a fracking site near Blackpool. Cuadrilla, a hydrocarbon explorer, had just restarted its operations after being shut down for a while by the regulators because of an increase in seismicity near the drill site.

Fracking involves injecting a pressurised water and sand mixture down a drill hole to open fractures in hydrocarbon reservoir rocks. The fractures allow natural gas, or oil, to flow in rocks that would otherwise be sealed tight to the passage of fluids or gasses. Bad hydrocarbon reservoir rocks can be made less-bad by fracking.

Frack Off.

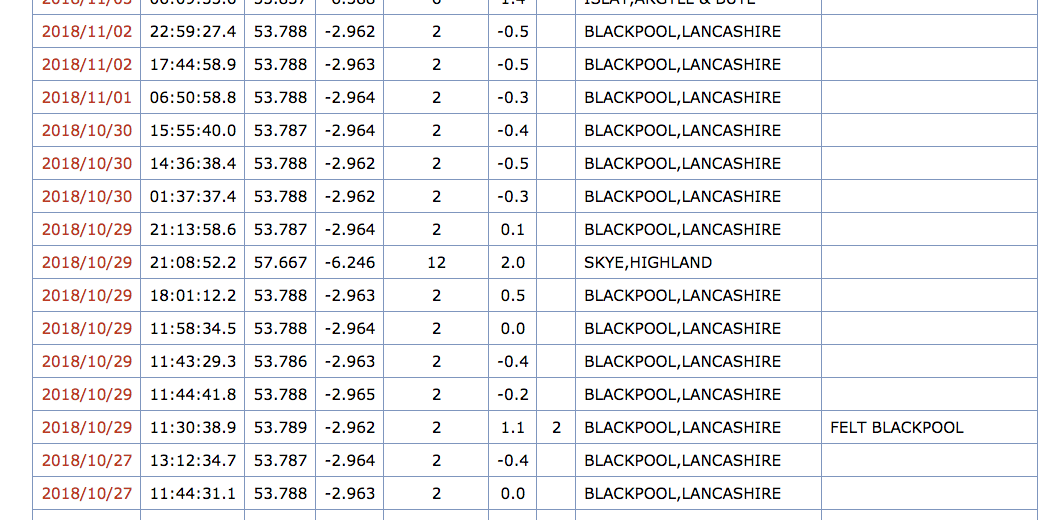

Almost immediately after fracking started up again, the British Geological Survey picked up a swarm of minor earth tremors that were gradually increasing in magnitude; nothing that you’d necessarily notice but they peaked at 1.1 magnitude in late October, which was felt by some local residents. The seismic log for the UK is linked here.

The October 2018 swarm of tremors near Blackpool is remarkable for a supposedly seismically stable area like Great Britain. The island does experience tremors from time to time, some of them quite large, but they’re mostly related to the British land mass still wobbling around after the removal of the huge weight of ice that covered it during the last Ice Age. But dozens of tremors in one small area is highly unusual and these are clearly man-made.

Under Pressure.

Fracking-related tremors occur because of one of the basics principles of structural geology: over-pressured water in fractured rock or along fault planes can, when the fluid pressure exceeds the strength of the rock, act like a lubricant allowing them to slide and slip, sometimes seismically. All very alarming I guess if you live near a fracking site, but also a very predictable outcome from structural geology theory.

Let’s Talk Rock Bursts

I’ve had a couple of I’m-a-bit-too-close-for-comfort experiences of rock-chatter. Both times were in the deep-level goldmines in South Africa when I was a twenty-something greenhorn geologist starting out in mining.

I’m not talking about the big mining-induced shakes we often felt after underground blasting operations. They were impossible to miss; a bit like a truck hitting the house (which in our case was 20 miles from the mine.) No, I mean I’ve been around the low-key evidence of extreme rock stress. These are signs that you don’t necessarily notice until you’re really close to the working face, but when you do notice, it’s best to pay attention to what the rock is trying to tell you.

It’s Called Popping.

One red flag for miners was what we euphemistically called “popping”. An overstressed rock face spontaneously spits out small chunks of rock at high speed, which make a pinging noise as they fly off. A bit like the ultra-realistic war movies where you can hear the crack of the bullet passing by a soldier’s head.

“Bits of volcanic rock did their best to embed themselves in our hard hats.”

It happened to me in a new vertical shaft (10 Shaft) we were developing on Vaal Reefs mine when it had reached a depth of about 3,000ft. I went underground with my buddy Paul from the rock-mechanics department to investigate some stability problems. When we got to the bottom, the drills were turned off so we could work. In the silence, it was impossible to ignore the random pinging noises as bits of volcanic rock flew off the wall and did their best to embed themselves in our hard hats. A few days later there was a much more serious accident at the same spot, when a large part of the side wall of the shaft spontaneously exploded outwards killing several people. The cause turned out to be a major over-stressed fault-plane near the shaft, cutting the Ventersdorp lavas.

It’s The Fault’s Fault.

The other time I saw signs of impending problems was much, much spookier and left a lasting impression on me. (Fortunately, there were no casualties the second time around.)

I was called underground by a mine foreman to visit a working face where his team had been having trouble supporting the roof. The face sloped down to where the gold-bearing reef had been cut off by a fault plane. There were no workers or drills going, so the place was completely silent as we discussed the issues he’d been facing. Mr. Miner told me quite calmly that the pit props he was installing as support were taking pressure within a few minutes of installation, the implication being that the roof of the stope was on the move. Never a good sign. And then came the kicker.

“Come with me” he said. “Let’s go down to the fault at the bottom of face.”

We crawled on hands and knees, about 50-60m down the face.

“Listen. You can hear the fault creaking.” Said the miner.

“Er…what?” I said, trying not to scream and run away.

“It’s creaking” he repeated.

Shiver Me Timbers

He was right. It was creaking. Clear as a bell, like timbers on a pirate ship in a storm. Seven thousand feet of rock above my head and there we were, with our hands on a fault plane that was moaning noisily about the stress it was under. That was beyond a doubt the scariest moment of my geological career; even worse than the taxi drivers in Tehran. We left, quicker than we came in and on my recommendation all work in that stope was stopped for 48 hours.

Two days later, a danger crew was put in to drill and charge up a single blasting round to move the whole face forward by a meter or so. The bluntly named danger crews got paid hefty bonuses that reflected the higher-than-average chance the crew faced of being buried under tonnes of jagged rock. They took on work that no sane person would go near with a long pole. They’d work a shift to drill and blast a round, then wait another day or two to see if the blast induced a tremor.

Hallo? Is That Vaal Reefs? USGS Here.

They charged up the face with explosives and it was blown at the usual time, 1 or 2am in the morning. Shortly after, my house mates and I were woken about the same time by the biggest earth tremor I ever felt in South Africa, a 5.2 magnitude shake that was detected by the US Geological Survey on mainland North America. They called up the mine rock mechanics department to let them know the magnitude just in case we hadn’t noticed.

The ceiling in my bedroom cracked and we rattled merrily for 20-25 seconds, a long time for mine induced bumps. The epicentre was on the fault we’d visited 2 days previously and a square kilometre of access tunnels and stopes was lost.

It pays to listen when rock is trying to tell you something.