Every composer worth their salt has a Requiem mass under their belt. What a cheerful bunch they are celebrating the inevitability of death, the eternal suffering of the damned and the terror of God’s wrath all laid out in impenetrable Latin. But, I’m willing to cut them some slack because the collected catalogue of requiem masses across the years includes some of the most iconic pieces of classical music ever written; Mozart’s Requiem is probably the best known with its brooding opening and its spectacular Dies Irae (Day of Wrath).

“Every composer worth their salt has a Requiem mass under their belt.”

It’s still unclear to historians exactly how much of the final version of Mozart’s mass was completed by him before he died, and how much was simply sketched* in by him, to be orchestrated later by his contemporary Süssmayer who, it must be said, did a damn fine job of completing the work and cementing its legacy as probably the finest Requiem mass ever.

*I’d never thought of musical sketches –small phrases or themes that a composer uses time and again- until I took a deep dive into Mozart’s catalogue and noticed how often he used similar themes, in different keys or rhythms, in many of his works. I guess it’s a bit like a great rock guitarist who knows his best licks and how to string them together into a knockout solo when he’s improvising. The composer had a mental notebook- or perhaps a physical notebook- full of musical tricks that could be used to tie up any phrase or movement.

In my seven years as a choir boy (bless!), we didn’t get around to tackling Mozart’s magnum opus. In fact, we only sang one requiem mass, the masterpiece by Gabriel Fauré, a French composer. It was written down in the late 19th Century and subsequently revised between 1887 and 1890. It’s far more understated than Mozart’s grander version, often using just the choir unaccompanied by the orchestra; for example, in the O Domine.

Coincidentally, I also studied the score of the requiem for my O-Level music qualification; the first and only time I’ve taken such an intense look at a classical music score from cover to cover. It gave me a lasting respect for conductors and their ability to read, hear and interpret incredibly complex scores and bring their vision of the score to full orchestral life.

Fauré lived to ripe old age of 79, dying in 1924, and had a distinguished, if slightly stop-start career. He lived through some of the most turbulent times in European history, avoiding service in the Great War because of his age and eventually rising to become head of the Paris Conservatoire. He is said to have suffered bouts of deep depression from his mid-30s on, fuelled by a lack of success as a composer, and by a failed relationship. Aside from his great Requiem mass, which in the modern era has been used in numerous movies, his most famous work is the Pavane which crops up less regularly in the media but nevertheless still gets regular airplay.

The impetus for putting the Requiem down on paper may have been the death of both of his parents between 1885 and 1887. Whatever the reason, Fauré himself claimed to have poured all his Christian faith into the piece. “Everything I managed to entertain by way of religious illusion I put into my Requiem, which moreover is dominated from beginning to end by a very human feeling of faith in eternal rest”.

If you’ve ever sung in a choir, you’ll know that choristers always have their favorite bits in any work; the movements or songs that they enjoy singing far more than the rest of the piece. It’s only natural; we all have our top songs on a well-loved CD, and so it is with choral works. If you’re in the audience, you won’t necessarily know which movement or section it is, but if you listen carefully and watch the choir closely, you can usually figure it out. The conductor lifts the baton, and suddenly you can see the slight smiles from the singers and the quick glances at their friends. That’s the signal. And when they sing, there’s a different energy – it’s more intense, sung with more gusto than the rest of the piece.

When we sang Fauré’s mass, spotty teenage choirboys, including yours truly, all loved the crescendo that kicks the work off. And what’s not to like? It’s a belter of an introduction, ending on a bright, powerful chord sung by everyone at the top of their voice, physically beating the audience into a religious trance.

But the real cherry for us on the back benches, what we loved best and I’m guessing it’s the same for most choirs who’ve tackled the piece, was/is the Libera Me. It’s a deceptively simple movement close to the end of the mass that took a while to worm its way into my brain, but in it went and it settled down and made itself totally at home.

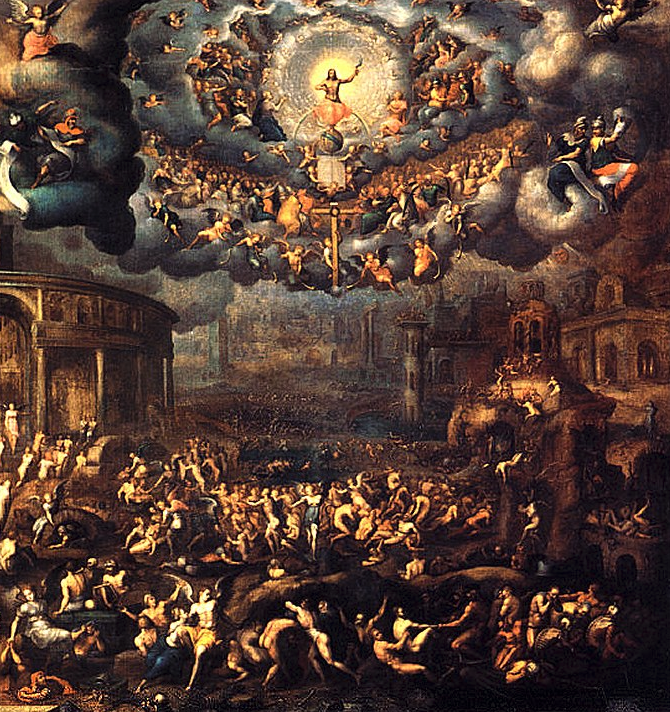

The translation of the specific Latin Libera Me verse is particularly cheerful, all death and fire and skies rent asunder by God’s judgement:

Libera me, Domine, de morte æterna,

in die illa tremenda, in die illa.

Quando coeli movendi sunt,

quando coeli movendi sunt et terra.

Dum veneris judicare saeculum per ignem.

Free me, Lord, from eternal death, on that terrible day, on that day. When the skies are to be moved, when the skies are to be moved, and the earth. As you’ll come to judge the world by fire.

What was it that we loved so much about this verse? Well, the score is a bit of a rarity in classical choral pieces. It’s sung by the whole choir in “homophony”, which essentially means everyone sings the same melody -bass, tenor, alto, soprano- and there’s no harmonization. You get so used to harmonizing in a choir that when you come across such simple scoring, it can be a bit of a shock. It’s quite brave of the composer to strip things down to a simple melody for each part. Everyone, for just a few seconds, gets to sing the same tune in unison –in different registers for sure- but the choir functions as a single entity. Nobody’s sitting around waiting for their thirty seconds of tenor or soprano harmonization while everyone else has all the fun.

We performed the Requiem twice. Once to the school and parents, and once when we recorded it in a nearby church to lay down a vinyl album to celebrate the school’s 180th(?) anniversary. We navigated the opening of the Libera Me and the mind-blowing power of the Dies Irae stuck in the middle. When the key verse comes, about 2 minutes and 50 seconds in to the Libera Me, it’s introduced by slow, solemn drum beats and single notes on the double bass and then you’re into it. Libera Me Domine. Glorious unity, everyone’s having fun and nobody’s left leaning against the wall waiting for a dance. The whole choir was waiting to open up and shout it out, which of course isn’t the point. That’s what the Dies Irae is for. The Libera Me is more reflective and solemn and builds in a slow crescendo as it leads into the final solo.

But Faure’s mass is much bigger than simply the Libera Me. I’m simply flagging what’s become the cornerstone of my memory of performing the piece. I’ve since heard the Libera Me sung by many performers on its own and obviously out of context. I listened to it recently at Covent Garden market in London, down in the basement by the Punch and Judy pub, and once in Edmonton by a singing waiter at a pasta restaurant. The restaurant patrons were convinced he was singing an excerpt from a great Italian opera and cheered enthusiastically when he was done. I didn’t have the heart to tell them they were actually listening to a depressing Christian reflection on judgement day.

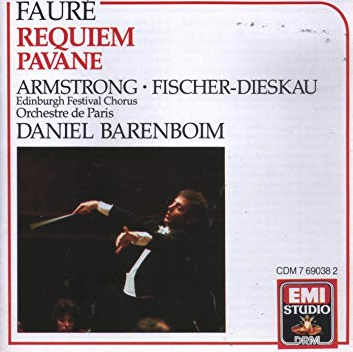

For what it’s worth, my favorite recording of the Requiem is from 1975. The great Daniel Barenboim conducting, appropriately, the OrchestreDe Paris.

„Pie Jesu“ from Faure‘s Requiem made me sit up and listen. Beautiful.