Things Geologists Do. Part 2.

Earth scientists are a well-educated bunch, although we don’t always come across as clever when we’re 5 beers in to our cups. Most geologists –other than self-taught prospectors- have some form of university degree. Many of my colleagues were so enamored with the University study-drink-drink-more-study-repeat routine that they did what I did, and went back to university to earn a master’s degrees or doctorate on top of their undergrad’ degrees. Clever bunch, geologists. But eventually, assuming you have no wish to be an academic geologist or a waiter, reality bites and some sort of salaried earth science career is needed to fund the pub breaks.

In June 1984, much to my surprise, I graduated with a decent degree. A few months later I was poking forlornly around the City of London, knocking on doors and handing out a naively-bad resume to any mining company that would take it. I got my break when Anglo American interviewed me minutes after I walked into their head office looking for anyone from HR to talk to. A month later I was on a plane to Jo’burg to start a 3-year contract as a mine geologist in the deep-level gold mines in what was then the Western Transvaal (now Gauteng Province). After 2 days in the city signing paperwork, I was shipped off to the small mining town of Orkney, where I was billeted in the single mineworkers hostel and unceremoniously thrown into the deep end as a shaft geologist on Vaal Reefs 5 Shaft.

They Were Big. Really Big.

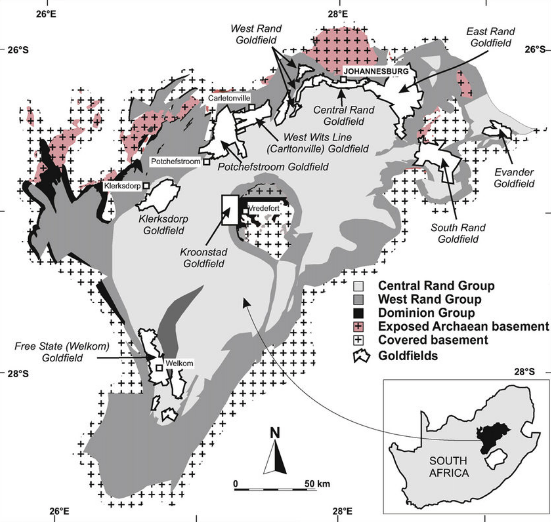

It’s hard to describe the scale of the underground gold mines in the Witwatersrand basin. They were, quite simply, huge. Many have closed since my time; they ran out of ore, or became uneconomic to mine when the gold price fell off a cliff in the 1990s. The deep mines couldn’t shave enough off their operating costs to still make money at $350/oz, unlike the low-grade open pit giants in places like Nevada.

When I arrived in 1984, Vaal Reefs had 9 separate shafts going down at least 7,000ft each, producing about 2.5-million ounces of gold per year. I ended up with the senior geological responsibility for a shaft that produced 250,000 oz. of gold a year, 10% of the total mine production. The mine employed about 45,000 people, many of them migrant workers drawn from across southern Africa, with 20,000 or so working underground every shift. Surrounding Vaal Reefs were three other large mines –Stilftontein, Buffelsfontein, Hartebeestfontein- all similar in scale. Sadly, accidents were all too common, with about 1 death per thousand employees per year, and on occasion they could be truly disastrous.

They Weren’t Fond Of The English

Mine planning meetings were held in Afrikaans, a version of Dutch; no allowance was made for me, the English geologist, because of the fractious history between the English and Afrikaners. Luckily I spoke reasonable German so the Afrikaans wasn’t too hard to pick up. Underground we spoke Fanagolo, a pidgin of various Southern African tribal languages with some Afrikaans and English thrown in to the mix. I went underground up to 4 times a week depending on the needs of the miners, assiduously avoiding certain areas of the mine which I considered too dangerous because of regular seismic activity (see my earlier blog post “Rocks can talk”).

My job as mine geologist was to supervise all geological aspects of the underground operations. Working closely with the surveyors, we mapped the advancing access tunnels, sampled the mine faces where the ore was extracted (although this was mainly done by the surveying teams), and interpreted the data so the miners were always “on” the ore body, or at least knew where their tunnels were relative to the ore. We also had drilling machines working for us, exploring ahead of the active faces to see if there were faults or folds, or pockets of pressurised water that might cause complications.

Bloody Hell, It’s Hot Down There.

This is all routine stuff that most geologists can do in their sleep with adequate training. In South Africa, it was complicated by the depth of the mines. I never worked shallower than about 5,700ft below surface, and spent most shifts around 6,000-8,000ft down. The deepest I went was a training course at 11,500ft below surface in the Carletonville mines between Vaal Reefs and Jo’burg.

With depth comes the natural geothermal heat from the rocks. The rock temperatures in the deepest newly-blasted faces could exceed 40 Celcius. Well-ventilated tunnels might be in the high 20s but poorly ventilated “ends”, ones that had sat for weeks not advancing, became fiercely hot and could get up into the mid-40s with high humidity. Oftentimes, you wouldn’t actually know how hot an end was until you got to the face of the tunnel to start work in the sauna-like heat. We took drinking water down in frozen 2 litre bottles which melted away merrily while we worked.

And Now… Shaft Sinking. Avoid It.

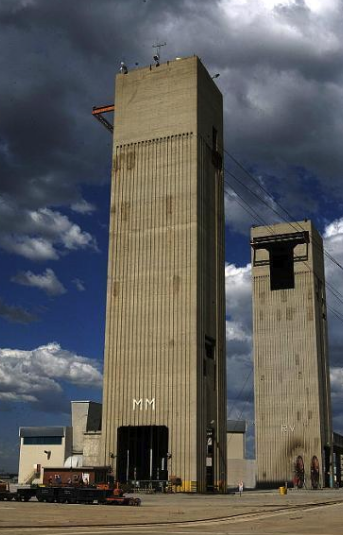

But vertical shaft sinking was by far the nastiest work environment I’ve ever experienced. It’s the digging of the vertical hole –thousands of feet deep- that serves as the main access to an underground mine. It’s the absolute sharpest, pointiest end of mining, with no room for error if things go wrong and can be quite terrifying.

I spent about 6 months on-call as a shaft sinking geologist on a new, deep-level gold mine that was under construction near Klerksdorp. Vaal Reefs 10 shaft was a twin-shaft system –one shaft for men and materials and cold air going down, the other for ore hoppers and warm air coming back out. The shaft was already about 3,000ft down, headed for a final depth of 8,000-or-so feet, and my job was to be available to map the rocks whenever there was a long enough break in the blasting schedule to allow me down, which happened every 45 vertical feet or so. “Available” meant any time, night or day.

When the phone rang, the Master Shaft Sinker would be on the line telling you to be there in an hour, ready to go. I’d turn up in my little blue VW beetle (God I hated that car, but that’s a different story), get changed and hurry over to the shaft clutching my note book, ruler, spray paint and pen.

Gotta Love Kibble.

You climb into a 5-6ft deep metal bucket called a kibble, and down you go, with whatever material or crap happens to be going down to the team at the bottom. To come out, you get in the kibble with whatever’s coming out. I once stood neck-deep in a kibble filled with 5 ft. of greasy, cold, drill water (try pumping water 3 or 4,000 ft. vertically.. not easy, hence the need for large buckets during development.) Other times you’d be perched on the lip of the bucket with your feet on a couple of tonnes of rubble being hauled up out of the hole.

Going down a sinking shaft for the first time is a very strange experience. You drop through the safety trap door at the top, which is there to stop stuff falling down and killing people. The door closes behind you, and everything goes pitch black. The kibble didn’t run on side rails so there was no sound or feeling of motion. If the shaft bottom is deep enough, it’s totally silent until you’re a few hundred feet above the work platform and the drills. Then, in a sci-fi moment, you start to see the floodlights, and hear the unbelievable cacophony of noise made by the drilling and the cementing crews who are lining the shaft with steel and reinforced concrete lining.

Great Gobs Of Concrete.

The bottom of a 3,000 foot deep, 30 foot wide vertical hole, with 8 rock drills going, is a hostile place. For a start, it’s cold. All the compressed air used in the rock drills is venting and decompressing, dragging the temperature down. Then there’s the noise: imagine 8 big rock drills in the front room of your house and you’ll sort of get the idea but not really. Sound wouldn’t bounce back from dry wall like it does from solid rock. I still suffer from slight hearing loss in my right ear which I ascribe to being a 23-year-old idiot geologist who didn’t wear earplugs.

And lastly, there’s the constant rain of shit from the 6-level working platform above you where the steel work and concreting takes place. Gobs of partly-set concrete, wood, bits of rock, the odd tool… it all falls to the bottom, so you’d better have your hard hat on and don’t stand too close to the shaft wall.

My work took 20-30 minutes to finish. You orient yourself to due north (the Master Sinker always knows where north is) and mark off every meter around the shaft with paint, like the numbers on a clock face. Then draw a circle in your note book, mark off the same numbers on it, and draw in the geological features relative to those numbers. Easy.

Bring Out The Jumbo.

But take too long and drillers would get impatient and drop the drill rig (called a jumbo) down from the platform, and start drilling the next blasting round. Time is money in shaft sinking – the mine needs to start producing ore as soon as possible to recoup the huge capital outlay needed to build it, and everyone gets paid production bonuses to keep things moving. Geologists stop stuff from happening so we can do our work, which isn’t popular.

Once the drill jumbo is down and the drills are fired up, you’re stuck at the bottom of the shaft until they’ve finished a full round. The jumbo is essentially a mechanical octopus with a drill on the end of each leg which completes gradually smaller concentric circles of holes, each around 4 meters deep. At Vaal Reefs, a full blasting pattern took about 3 to 4 hours to complete. So if I took too long and missed the last kibble out before the jumbo dropped, I was stuck there, standing up for 4 hours, cold and deaf, with 20-30 guys and 8 drills. A total nightmare, which happened a couple of times over the 6 months I was on call.

I Had It Easy

But on balance, I had it relatively easy. A colleague once told me his experience of working on a new shaft at Western Deep levels, which was heading down to a final depth of 14,500ft below surface – two and a half miles- with 2 vertical shafts and an inclined adit to finish. He was mapping the second vertical shaft down at about 11,000ft. They’d begun to cut a mining level so he had a side tunnel to map. Stepping back into the shaft from the side tunnel, something landed a few feet in front of him. Surprised by it, he looked up and noticed the drillers all standing completely still as other objects landed around the shaft bottom. Somebody had accidentally let some steel H beams drop down the shaft and after falling 3,000ft, bouncing off the sides of the shaft as they fell, they’d turned into steel lumps and had blown through the working platform like cannon balls. The drillers know there’s nowhere to run when something falls down the shaft, so their instinct is to stand still; they either get hit or they don’t. Luckily nobody was hurt.

As I said, nasty and hostile -that’s shaft sinking- but I’ll never regret doing it.

Don’t Forget

As ever, if you even remotely like what you’re reading, you can subscribe to urbancrows.com via the insultingly small subscription box that I somehow managed to place near the top of the page even if I haven’t worked out how to format it yet. And I doubt I ever will. I’ll be sure to email you every time I post another 1,500 words of dull geo-speak. You have nothing to fear but periodic boredom.

Write a book! It‘s so interesting!