I spent last weekend lolling around in the sunshine at the Vancouver folk music festival, down at Vancouver’s dusty Jericho Beach Park. It’s a wonderfully scenic spot for a fun weekend of eclectic music, watched by an equally eclectic Pacific Northwest crowd. People who wouldn’t normally be seen dead in a tie-dye T-shirt dose themselves in patchouli oil and let their inner hippies out of the artisan-crafted, organic bamboo box for a couple of days. Unfortunately, on hot weekends there’s nowhere in the festival grounds to hide from the blazing sun, so most sane people eventually gravitate to the beer garden for a cold brew and the safety of the sun umbrellas.

The north side of the beer garden is the business end, lined with grey and blue plastic jiffy johns; on warm days, they turn into scorching hot chemical-scented saunas. God help anyone who’s unfortunate enough to get stuck in one.

Mmm. Cider.

Mid way through the afternoon, some friends and I were sipping on cold ciders provided by the fine people at Persephone brewing (highly recommended) when the toilet cleaner showed up. A rather forlorn looking guy in overalls was working his way along the line of loos, understandably resentful that he wasn’t able to quaff a frosty one, but instead had the job of removing the end product. He connected a hose to each toilet in turn, and emptied the blue chemical soup into a nearby tanker truck. Lucky man.

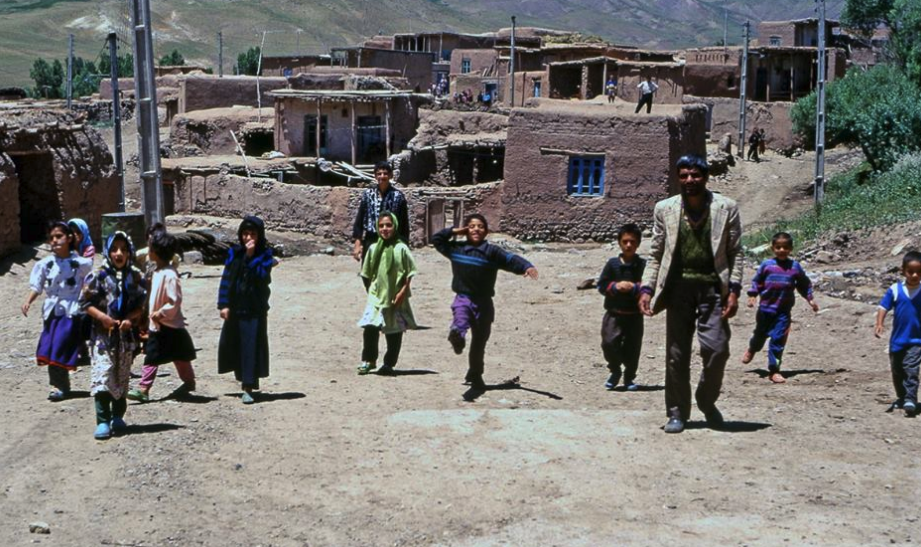

Watching him drain the bogs took me back to a sewage-related incident that happened to me in the 1990s in Iran, at a gold exploration project I was managing about 6-7 hours drive north of Tehran.

We’d built small drill camp, big enough to house a crew of Australian drillers, geologists and various other hangers-on. The drilling conditions were challenging so we’d hired an experienced technical drilling consultant to help out. He was a huge bear of a man from Australia called Dave.

It’s Got To go Somewhere.

We were puzzling over the problem of sewage disposal until Dave stepped in and sketched out his tried-and-tested design for a septic system for field camps. It involved 2 pits lined with bentonite clay, and some pipes and connecting channels. It was the only practical solution we had, so I hired some locals with shovels to build it and we were finally able to connect up the mud-room, toilets and showers.

Inevitably, after a couple of months use, the septic tanks were full and needed to be drained. We were about an hour’s drive from the nearest town that had a tanker truck to handle the job, so we arranged for the “company” (I use that term lightly..) to come by and pump it out.

Unusually for Iran, the driver showed up on time. He stuck a large pipe into the first pit, fired up the pump and partially drained it, filling up his truck’s small tank. He announced that he had to go and get rid of the first load, and drove off at an alarming speed (bearing in mind the nature of his load) down the steep mine access road. The nearest town was Takab, an hour away, so I mentally allowed for 2-3 hours before he’d be back. But ten minutes later he was back with an empty tank, and started pumping out a second load.

At this point, all sorts of alarm bells were going off in my head. The burning question was where the fuck had he emptied his tank? A few thousand gallons of fermented poop isn’t easy to hide, so I called over Payman, my English-speaking Iranian colleague, and we investigated.

It’s Not Where It Should Be.

The driver had pulled off the road, 5 minutes down from the mine, and emptied the entire load in to the local stream; the same local stream that the villagers (our labour source) got their water from, and that eventually fed a small fish farm where they reared trout. To be fair, the stream contained alarming levels of arsenic from the waste dumps of the small orpiment mine we were investigating, and we’d advised the locals not to drink from it, but it didn’t deserve further contamination.

We remonstrated with him.

You can’t do that. I said.

Fine. He said. I won’t do it again.

Good. I said.

He pumped out a second load from the septic tanks and off he went. This time he was back after about half an hour and once again he obviously hadn’t driven to his facility in Takab. More questions were asked.

This time, he’d driven a little further down the road to a local beauty spot – a small cave by the side of the road with a fresh-water spring, where the villagers went to have family picnics. The cave over looked the newly-stinking stream, the one local kids used to splash around in on hot days. After running his hose into the cave, he’d pumped the second load of waste into it, turning a happy family gathering place into a festering swamp of liquid shit. He’d then stopped for a cigarette and waited long enough to make me think he’d done the job properly.

I didn’t let him take a third load.

This is a crappy story.

yuck yuck