A Tale Of Equipment Lost

Production is everything in mining. Sorry, I meant to say that safe production is everything. You can’t make money from a big hole in the ground if nothing useful is coming out of it and people are getting hurt.

Anyone who’s worked down a pit will eventually feel the pressure from higher up the food chain to produce more of whatever it is you’re mining. Sometimes the pressure will come from the stroppy, loud-mouthed chief mining engineer shouting at everyone when the mine is below quota. Or perhaps the plant head-grade will be changed constantly, necessitating closer geological control; a panicked attempt to get more ounces through the plant. I’ve experienced both.

But the deeper you go, the more important round-the-clock production becomes. In the deep-level South African mines, any prolonged production stoppage inevitably led to closure of some of the access tunnels and production faces; it’s a natural consequence as stressed and pressurised rock expands into any empty space that comes its way. This partly explains why mine workers’ strikes were often so effective in South Africa. Mine management knew that a long work stoppage would result in the need for costly redevelopment of large swathes of underground workings.

Everything Is Old.

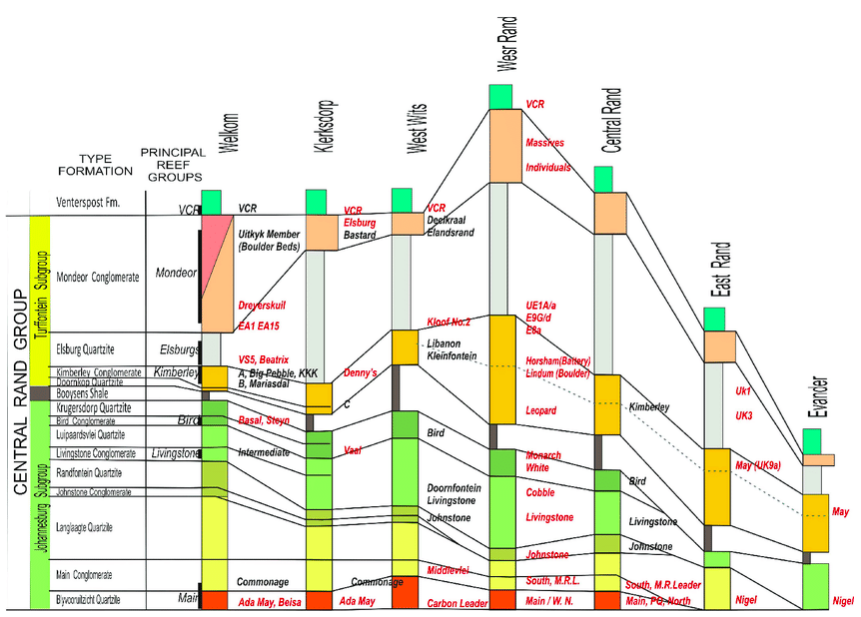

In about 1986, Vaal Reefs 2-Shaft needed more production. We exploited the eponymous Vaal Reef, a relatively high-grade gold reef about 1-2m thick and a couple of billion years old. Two Shaft was originally sunk in the 1950s (I think -anyone know for sure?), so the bulk of its capital costs had been paid off years back. Hence, we were a low-cost contributor to the broader mine production, which was then running at an astonishing 2.5-million ounces per year. As a consequence, we were under constant pressure to up the ounces mined, and management was always looking for new sources of ore to boost our production quota.

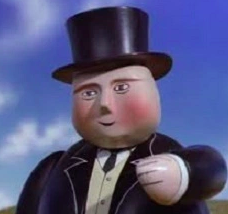

One sunny but chilly winter’s morning, the Fat Mine Manager turned up at the 2 Shaft offices in his huge company Mercedes, fresh from his huge company house on the manicured company golf course. He was accompanied by the production manager for Vaal Reefs East and assorted other minions, all looking suitably shit-scared. The Fat Mine Manager had a reputation for breaking desks when his temper got the better of him and something was clearly up.

A Fat, Bad Tempered God

At this point in the story, it’s important to get your head around the deeply ingrained South African myth of the infallible mine manager. Senior management were treated like Gods, albeit Gods that ascended to their lofty, well paid thrones by being better at shouting and banging on tables than the other Gods. Mine management was almost Soviet in its hierarchical structure; many lower and middle managers would never dream of questioning the decisions made by the top men on the totem pole. Senior management were almost always referred to as Meneer (sir) by subordinates.

I never got the deference, and neither did many of my ex-pat colleagues. Growing up in 1970s Britain, and suffering through a strict boys’ grammar school education, I flatly refused to call anyone “sir”. Mr This or Mr That, yes, but sir..never. I was also imbued with a Monty Pythonesque cynicism for bombastic leadership, which made it hard sometimes not to laugh at the top brass when they were in full shouty-screamy mode.

The Trickle Down

Back to the story. After a couple of hours of muffled shouting from the shaft offices, the Fat Manager climbed into his royal carriage and left, looking redder and sweatier than when he arrived.

Then the trickle down began. As senior geologist, I was called in to see the Shaft Manager who was a bit of a drama king, totally in thrall to the Fat Mine Manager. He was constantly nagging the geology department to explore for new production areas. All good and well, but we were faced with some complex structural geology puzzles to solve –fault loss areas where blocks of ore might be hidden that needed extensive drill testing- and the mining engineers weren’t by nature very patient.

He’d been told in blunt terms by the Fat Manager to look at the feasibility of mining one or more of the other gold-bearing reefs in the sedimentary package. More tonnes. More ounces. We don’t fucking care where they come from, just get them, was the message. Off we toddled, back to the geology offices, with a super-sized flea in our ears, and got to work looking at the old plans and stratigraphic columns for 2 Shaft.

I know, Let’s Mine Denny’s Reef!

A few hundred meters stratigraphically above the Vaal Reef was another gold-bearing conglomerate known as Denny’s Reef. In sedimentological terms, it wasn’t as well worked as the Vaal Reef and was polymictic rather than monomictic, so the prevailing metallogenic theory for the Wits basin said it should be thicker and lower grade. So, there was potential to mine higher tonnages to make up for the lower grade. Two Shaft had mined Denny’s in the 1950s from the higher working levels, so the decision was taken to go back in on 53 or 55 level, if memory serves me. (The level numbers referred to the depth in feet below mine datum –essentially the surface- so 53 level was 5,300 ft down, 55 was 5,500 ft down and so on. )

We devised a cunning plan to investigate an old production stope that the maps said had been stopped while it was actively mining Denny’s Reef. If the face was still on ore, we’d be able restart production fairly quickly. Another plus was that access was via one of the shallower levels, “only” 5,500ft below surface, so the workings would probably still be open, assuming they were properly supported in the first place.

Breaking Down Walls

We put together a small team to investigate – me (the token geologist), a Mine Captain and a Shift Boss, a ventilation engineer plus some labourers with sledge hammers and pinch bars to break down the wall that now blocked the access.

The cage didn’t stop at 55 level so a special trip was needed, coordinated with the banksman who controlled the lifts (known as cages.) The day came, and we were dropped off at 55 level. After checking that the ventilation was still working we walked in about a kilometer to where the Denny’s Reef access cross-cut split off from the main haulage way. I was checking the geological mapping along the route and it all looked accurate. We were in the right part of the sedimentary stratigraphy to find Denny’s reef.

Once we got to the walled-off end of the cross cut, the Shift Boss instructed his small crew to break down the cinder-block wall. We could see that the ventilation pipes actually went through the wall and hadn’t been disconnected, so the ventilation engineer trekked back to the nearest fan and switched it on to give us air flow once we got in.

Good Lord, What’s That?

The level we were exploring had last been mined in the 1950s. It was one of the oldest parts of Vaal Reefs and had sat abandoned and unloved for decades. But when the first cinder block was smashed out of the wall, a bright beam of light shot out through the hole, which came as a bit of a shock. A lot of “what the fucks” were uttered, rapidly turning to laughter, as we double checked that the last active mining had been in the 50s. Yup. We weren’t wrong. So why the lights?

Eventually we had a hole big enough to climb through. Then things got stranger.

Behind the wall was a waiting place, where the miners would change at the start and end of their shift, eat and have a smoke. The daily mining plans were normally posted on the notice board there. Whoever worked there last, presumably the crew that bricked up the tunnel in the 50s, left the lights on and they were still burning 30 years later. There were also newspapers from 50s, tools, a set of overalls, hat lamps. The only thing missing was a bearded miner. “I’ve been waiting for you. I’m gagging for a smoke.”

Anyone Seen A Train?

Bizarrest of all was the electric ore train that had been parked up, switched off and simply left there, with 5 or 6 hoppers full of gold ore. This was a big piece of kit and an expensive one to boot; a multi-tonne, battery operated loco, standard underground equipment for hauling mineral to the ore chute at the shaft. Apparently nobody ever missed it on the equipment inventory or in the weekly planning meetings.

“We’ll be using Loco 5. Anybody know where it is these days” Cue lots of down-cast eyes and uncomfortable foot shuffling.

“Nope, no idea. Haven’t seen it in years meneer…I think they took it to 3 shaft. Frikkie? Any idea?”

“Uh-uh. I heard it was on 78 level. We’ll.. er… check”

All they had to do was move the train 10 feet before they built the wall.

After a few hours delving into the old stopes, it was obvious that re-equipping and mining would be feasible. But in the end, when the assay numbers came back it was lack of grade that killed the Fat Manager’s ambitions for Denny’s Reef.

Far as I know the loco is still there.

Don’t Forget

As ever, if you read this without falling asleep, you can subscribe to urbancrows.com via the horrible subscription box that I somehow managed to place near the top of the page even if I haven’t worked out how to format it yet. And I doubt I ever will. I’ll be sure to email you every time I post another dreary 1,500 word memoir. You have nothing to fear but periodic boredom.

That was hilarious! Well written, as always. Ag, arme ou “Frikkie”. There was always a Frikkie on the team. The myth of the Infallible Mine Manager indeed. I recall going to a tea party for women grads hosted by the wife of one of the Kloof GM Mine Managers at the Mine Manager’s Mansion. The house had security guards, a long driveway, lawns like golf greens, many rooms full of grand furniture, and hot and cold running servants in uniforms. That was what we were all supposed to aspire to – the husband’s rank, the mansion, the social status and the money. Those were the weird old days.

As always, enlightening and entertaining. Keep writing!

We had a decent crack at mining the ‘C’ Reef in the early 1990’s at 2#. Grade was never the problem, but tonnage was – it was 20g/t over only about 1 or 2 cm, so only 4-500 cmg/t over a narrow stope. We tried using diamond wire from quarrying to extract very narrow slots, but tonnage killed that idea.

Napoleon ‘Nap’ Meyer (aka ‘God’) was GM at Vaal Reefs during my time.

Never knew Meyer. I’ll refrain from naming the manager during my time..!

Extremely accurate description of the hierarchical situation on the Wits gold mines! I could always find it very funny because I never worked directly in any of those systems. But even slightly removed, in ore evaluation, I could relate. I recall reefs being mined with inappropriate methods (large trackless excavations on narrow, variable-width, variable-grade, faulted Kimberley reefs, for instance) but somehow the resulting disappointing grades were always the fault of the geologists.

Please keep these stories coming!

Thanks Ron. Feedback always appreciated! I have lots of stories but eventually my addled 56-year old memory will run out of Wits ones.