Along the edge of the tideline.

Shuffling along the winter tideline, layered in strata of sweaters and a damp anorak, I finally spotted what I was looking for; a small, rounded translucent orange pebble maybe 1cm across. It winked seductively at me from a pungent bed of rotting seaweed. I was thrilled. It was my first piece of North Sea amber.

I didn’t find amber often, just regularly enough to keep me coming back to the beach near my home in all weathers, stumbling along -eyes to the ground- oblivious to the cold and rain.

It was one of my nerdier phases as a kid -and God knows I had some really sad ones. When my teenage buddies were leafing through torn copies of girly magazines and puffing on illicit ciggies down the alley behind Woolworths in Ramsgate, I could be found grubbing about on the beach looking for fossils and amber. (Yeah, well, mildly inaccurate. I did have a well-thumbed magazine stuffed under the mattress and I had started smoking at 14, so all is not lost.)

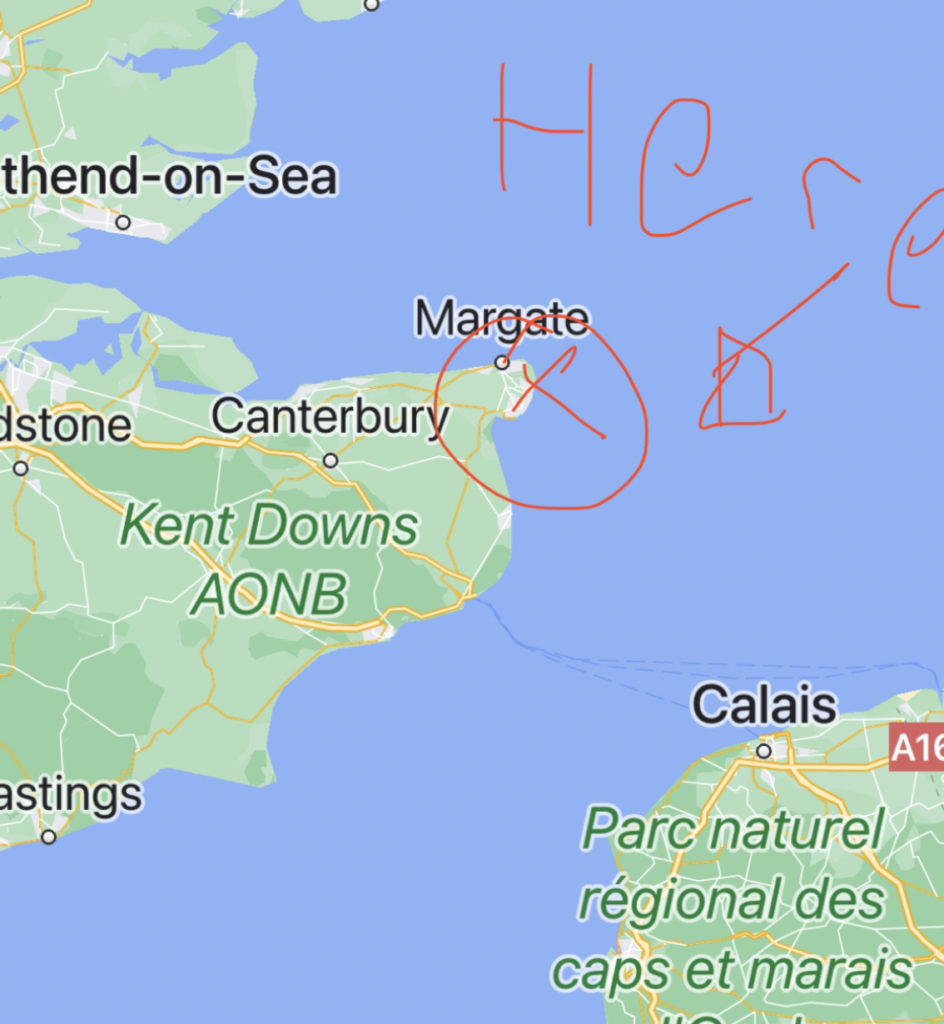

The Isle of Thanet

I grew up in Broadstairs, a small beach town in southeast England. Every summer it’s invaded by thousands of day trippers from London who head down the sloping high street to the beach at Viking Bay clutching buckets and spades and floaty toys. It’s a curved strip of sand -the focal point of the town- butting up against a crescent of white chalk cliffs. I spent many happy summer days on that beach with my mates, chasing girls, drinking whatever hooch we could nick from our parents, and pretending we were more streetwise than our middle-class Grammar School upbringing would suggest.

Broadstairs is one of a handful of small towns that make up the Isle of Thanet. Despite the name, Thanet hasn’t been an island since Roman times when the water way which separated it from the mainland silted up. Thanet is just about the closest point to France in Britain; a perky geographic nipple 20 miles east of Dover crowned by the glorious North Foreland lighthouse, a classic octagonal white painted pharos, still in use, that helps to guide ships on their way up the English Channel (although we switch it off when French ships go past. Because.)

It’s underlain by bright white soft chalk, cut through with black bands of flint nodules that look like the layers of filling in a sponge cake. The chalk is roughly 85 million years old: Santonian in age and part of the Upper Cretaceous (if you must know.) And it’s packed with fossils -calcified reminders of a time when southern England lay submerged beneath a warm, tropical sea teeming with marine critters.

Indiana Rushton

The fossils are easy to chip out of the soft white stone, but they’re very fragile. All I needed to pass myself off as a seasoned fossicker -Thanet’s own Indiana Rushton- was a small hammer, a chisel and a ratty old toothbrush to scrub away the remnant chalk when I found something. Round sponges, ivory-coloured sea urchins, horn corals, bivalves (oysters) and crinoid stems segments emerged from the chalk. I’d rush home to clean them and file them away in match boxes in my bedroom. My burning ambition -alas, unfulfilled like many of my life’s goals (sigh) – was to find a complete fossil crinoid with the stem and the medusa-like fronds intact, but all I ever found were stem fragments. Still, I was happy with my modest successes.

If I was really lucky, my mum or dad would drive me 45 minutes west to the harbour town of Folkestone -a depressed dump then and now- where I’d wade around in the muddy sediments of the Lower Cretaceous Gault Clay, exposed under the scenic Leas Cliff. The soft clay “rocks” – 100-million years old – were formed as sea levels were rising across what is now Europe. They contain a huge abundance of marine fossils and are studded with particularly gorgeous pyritized ammonites that are washed out of the clay by the sea and catch under rocks. Turn over enough rocks and you’ll find handfuls of the lovely, glinting metallic spirals.

It’s All His Fault.

My formative geo-mentor was Mr. “Tex” Willard our chemistry teacher. He kept a small collection of crystal-samples in the chemistry prep room: chunks of the common sulphide ore minerals used to perk up some of his chemistry classes. He allowed me to come and gape at the crystals each lunch time, and I’d dream erotic dreams about having my own collection one day (one dream that I DID fulfil.)

Tex was a tad eccentric and would often tell us that he preferred decoking his 2-stroke outboard boat motor to having sex with his wife -all a bit weird in a boy’s school grade 10 chemistry class. But he DID know a bit about minerals and fossils so I forgave his priapic failings. I didn’t know a single actual geologist and as far as I was concerned Tex was The Man.

Everything was going well for me. I’d show Mr. Willard my new fossil finds, and he’d pronounce “bivalve” or “echinoid” as I nodded sagely in agreement. Then one day he uttered the fateful words

“Have you found any amber yet?”

What? Amber? Good God why hadn’t he told me before? No, I hadn’t found any, but fuck me, I was going to. And just like that, a few careless misplaced words began a years-long obsession with beach combing, about as Zen a hobby as you can hope to find.

(Actually, I had 2 ambers in my teenage life. A summer or two previously, during the scorching hot June and July of 1976, I’d had a serious crush on a girl called Amber who I met on the beach. She strung me along for a while and then flatly refused to go to the local flea pit cinema with me for a snog in the back row, scotching my hopes of a teenage relationship. The other amber was a little more giving and has stood by me for a long, long time.)

It’s Best When It’s Stormy

He told me to wait until a storm had come through the English Channel, and then to walk the tide line a few days later to comb through whatever flotsam was washed up with the storm-tossed seaweed. Amber floats so it ends up high up the beach with whatever else the waves carry.

Off I went a few weeks later a couple of days after a nasty channel storm. I walked for a few hours, at a snail’s pace, hunched over like an aging monk walking a damp cloister, and dammit if I didn’t find 3 or 4 pieces of lovely orange amber. The biggest was about an inch in diameter. It was clear and milky and swirly and beautiful, and so so easy to polish as I discovered when I got home. Some fine grit paper, a nail file and a bottle of brasso and an hour of rubbing later and I had a shiny polished nugget of amber to impress my parents. I still have that piece, set with a small gold ring so my mum could wear it as a necklace.

It Smells Good

The wonderful thing about amber is its smell. Take a nail file and rasp away some amber dust and you’ll smell the resinous sap of ancient trees. It’s made up of natural resins “organic compounds, including alcohols, ketones, carboxylic acids, and most notably, unsaturated hydrocarbons known as terpenes and related terpenoid compounds. Monoterpenes, isomers with the formula C10H16, consist of two isoprene units [CH2=C(CH3)CH=CH2]. The majority of resins consist mainly of compounds based on diterpenes, C20H32.“

Marvellous: a chemical way of saying that fossils are amazing things, but actually smelling amber, something that old, is truly bizarre. Each time I worked a piece I was dragged fragrantly back millions of years to an age when huge bloody reptiles stomped around in primordial forests- it was mind-blowing for young teenager with a festering interest in geology.

Where the F*ck Is It From?

At the time, I had no idea where the amber came from. I developed my own theory that it was washed out of coal beds exposed on the bed of the English Channel. The storms would dislodge it and sail it reluctantly to my beaches (amber is less dense than sea water and readily floats). But it was always rounded -presumably because of plenty of time spent at sea or being bashed around on other beaches. Some researchers believe that the amber I found was scraped up by the ice sheets of the last Ice Age as they ground across Scandinavia and the Baltic, depositing it in glacial clays and sediments, now offshore where they’re eroded from the sea-bed. Who knows? I like my theory because I also found a lot of sea coal; rounded chunks of salty coal that would burn if you tried hard enough to set them afire.

It’s All Tex’s Fault

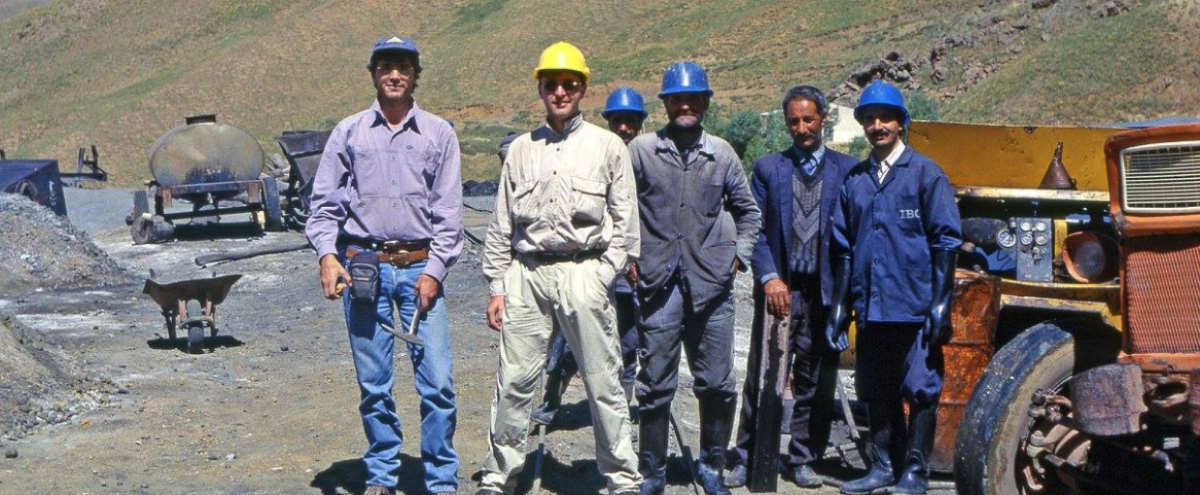

Apparently, Tex is still alive and living in Margate on the Isle of Thanet, although he must be well into his 80s by now. I have a lot to thank him for. His encouragement, and the obsession with crystals and minerals that he sparked in me, eventually led me down the road to what became a very satisfying 40-year long career in mineral exploration.

And Remember…

If the smell of rotting seaweed that permeates this nostalgia sodden piece hasn’t put you off my dreadful website, please subscribe to my blog using the subscription box that’s happily bobbing along in the virtual ocean at the top right of this page. You’ll be sorry whether you do or don’t so you really can’t win either way.

Dear Ralph,

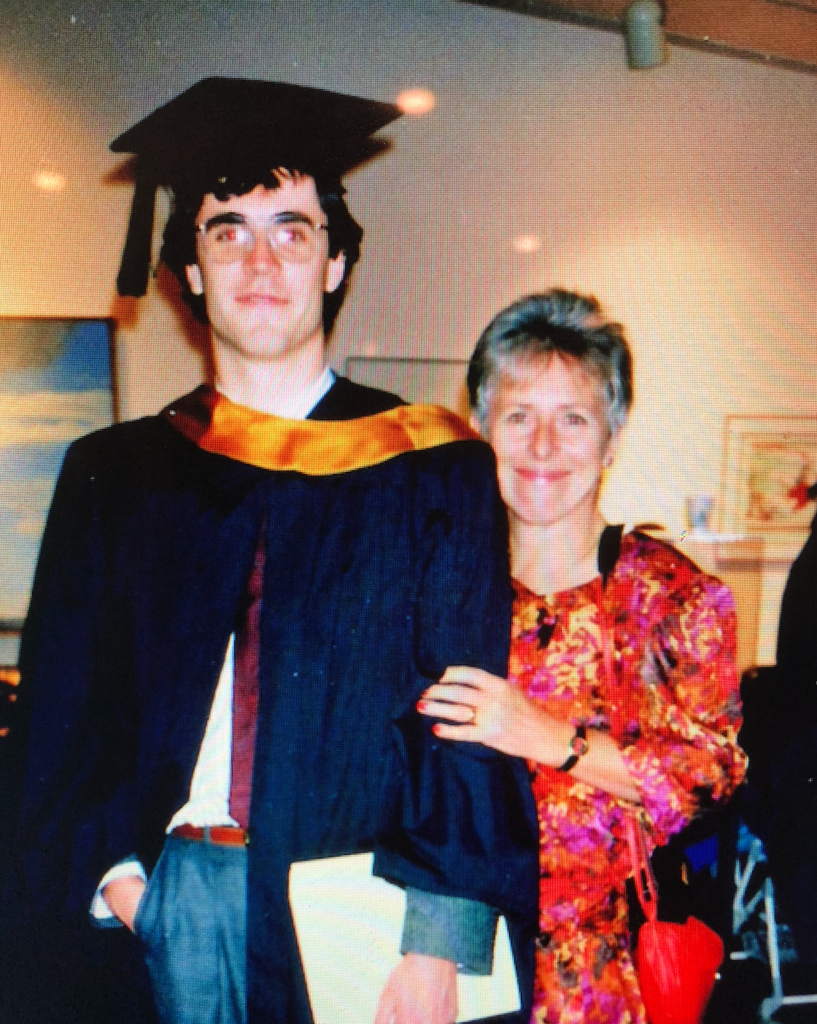

very romantic post, very well written, love it, one can see that you miss your mom, that you’re thinking about you own life as you age, you’re a great writer, really, and the resemblance with your father is astonishing, on the first picture I thought you were your father.

On a side note, I will be going to Bulgaria soon, and will prospect for gold in the Vladaya river.

Maybe you yourself went prospecting there, and maybe you know some hotspot or two, so to speak.

I’m looking forward to your next Blog post

Many thanks for the kind feedback nick. Much appreciated. Never worked that river so I can’t give you any advice on where to look. We were hard rock prospecting

Thanks Ralph,

well, I’m just a student with a gold pan, but maybe I will find the golden potato, haha.