Turkey (*now known officially as Türkiye) -a country I know fairly well and have always loved visiting- has been on my mind recently for both good and sad reasons. I’d just finished this piece when word broke about the terrible earthquake in southeast Turkey and the awful loss of life it caused. If you can, please donate to the relief effort via the Red Cross here. And thanks to my “abi” Dave C. for the photos in this piece. For the life of me I have no idea where my photos of Turkey have gone and it’s pissing me off.

Slogging up a steep forested path in northern Türkiye, I was focused on the outcrops along the side of the path, checking for signs of mineralization. It was a dry, crisp mountain morning as my Turkish colleague and I headed on up through the woods toward the tree line, crossing creeks clogged with avalanche debris. I was feeling a bit worse for wear -still on the mend after a 2-day bout of food poisoning I picked up just after I arrived in Ankara- so the walk was a welcome distraction from the aches and pains.

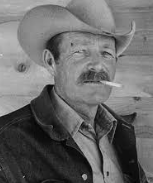

As the new boy in the field office, I was paired with a chain-smoking experienced local geologist. He was a small chap who bore an unsettling resemblance to Hassan Al-Assad, the murderous former president of Syria and I never quite shook the feeling that I was doing field work with a moonlighting genocidal dictator. He smoked a lot -a 40 a day habit- so we were permanently shrouded in a blue cloud of Marlborough smoke which put a bit of a nicotine-scented damper on the fresh forest air. He also ate very little during the day as the nicotine suppressed his appetite. I’d have to insist we stop for lunch: me, a can of tuna and packet of Ulker-brand chocolate biscuits washed down with cherry juice from a box, and him 5 more ciggies. I’d sit there munching on oily fish, praying that he didn’t commit an atrocity while my back was turned.

Goo.

As we trudged upwards making idle chit chat about the rocks, I began to see small puddles of clear goo here and there along the stony forest track. They looked like stranded jellyfish -not generally native to mountain ranges- or the silica gel inside a damp nappy (diaper, for you North Americans). Occasionally the gelatinous splotches would be flecked with blood so it was definitely 100% animal product, but there were no other clues as to what might be producing the slime.

Then, rounding a bend under a canopy of tall pine trees, we saw a goat -a miserable looking specimen- on its side in the middle of the path watching us with wide-eyed suspicion. It was small, bearded and wiry with a huge, distended belly, not dissimilar to Jim, the old boy who ran the local fish and chip shop in my hometown when I was a boy, but I digress.

Every few seconds it lifted up its head, quickly checked on our whereabouts, and let rip with a pained gurgling bleat that hinted at some serious discomfort. Sticking out of its back end was a pair of tiny hooves.

We stared at the goat for a minute or two as it tried to birth its kid, silently contemplating the miracle of new life while it glared helplessly at us. It was a perfect David Attenborough moment -the trees rustling seductively above us, more goats bleating in the forest- which was rudely interrupted by a dirty-looking shepherd boy wearing cheap rubber shoes that looked like they were made from car tires, who emerged from the woods in a cloud of flies. Making a beeline for our goat, he stopped dead in his tracks when he spotted us, a Turk and a..er..a foreigner. He quietly asked Mehmet who/what/why I was and stared at me intently when Mehmet told him I was yabanci, a foreigner.

The curious boy was accompanied by dozens of uncurious goats wearing bells that clonked and bonged as they tumbled down into the road. He stomped up to our 4-legged friend, bent down, grabbed hold of the emerging hooves and dragged the kid out with an experienced yank. There was plenty of goaty eye watering, lots of bodily fluids and a shit ton of frenzied bleating from the mum. Then out popped the kid along with a small jelly-fish sized blob of clear stuff, the afterbirth. Jellyfish mystery solved.

What Was I Doing There? I’m Glad You Asked.

The year was 1993 and I was in Türkiye working for Rio Tinto, based out of Ankara. Our modest team was focused on regional exploration for copper, zinc, gold and silver in the Pontide mountains along the northern Black Sea coast. Cominco had all the good ground staked, over 80,000km2 to their name, so we were playing catch up when it came to prime exploration territory. Rio was one of 3 or 4 of western mining companies that had set up shop in Ankara, hiring local and expat exploration teams to explore the country for metals. Anglo American, Cominco, and a handful of gold ExploreCos were also kicking around; the vanguard of a bigger Turkish gold rush that kicked off a few years later in the noughties.

From my perspective it was a well-paid gig – a hundred pounds a day, mostly tax free. After a few years of graduate-student poverty it was a welcome windfall for me. To be honest, I was so hard up by that point I’d have happily licked the tables clean in my local pub for spare change. My mum was sick of me living in her cramped country cottage in the ancient Kentish village of Barfrestone. And I was sick of the smoky social security office in run-down Dover and my 35 quid-a-week dole cheque which didn’t go very far. Plus, my only previous job before graduate studies in Canada had been 3-years down the South African mines so this was a chance to do real geology in an amazing location that I’d never visited before and get paid. The easiest no brainer of my life. Off I went.

The Pontides.

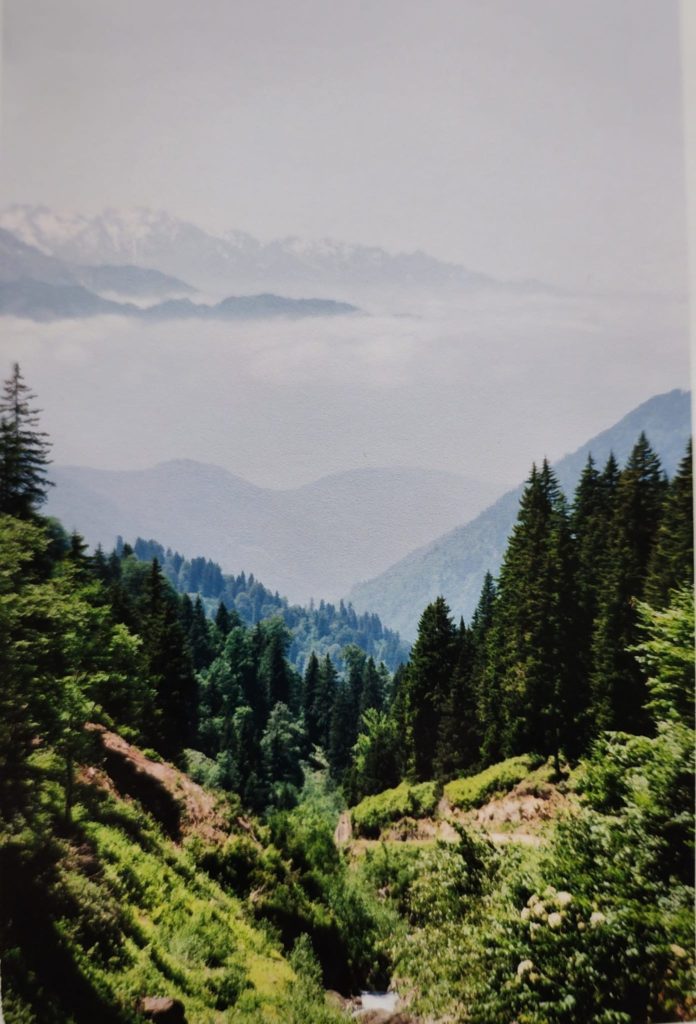

The Pontide mountains form an arcuate range of peaks that stretches for hundreds of kilometres west to east along Türkiye’s northern Black Sea coast. They reach up from the sweaty humidity of the Black Sea to gorgeous high alpine meadows and ridges, touching nearly 13,000ft at the top of Kaçkar Dağı south of the port of Trabzon*. We’d base ourselves out of towns along the Black Sea like Rize, Cayeli, or Trabzon, and drive our little Lada Niva 4×4 trucks south from the sea up the rough mountain roads, prospecting and following up satellite photos of the volcanic rocks looking for unusual features that might be related to the presence of acid-weathering sulphide ore bodies.

*Trabzon was a particularly fun spot with its Russian market, the Rus-pazar, snaking along the garbage-strewn sea front. Russians and Georgians would cross the border from Georgia and set up stalls to sell anything they could, literally anything. You could buy chemical warfare suits, tins of Russian caviar for five bucks, cheap vodka that turned to ice in the freezer [ho hum…live and learn] and long strings of white or pink cultured pearls for $10 a string.

At sea level, the Pontide foothills are lush and green, draped in deep-green tea plantations and sprawling orchards bursting with hazelnuts and cherries which thrive in the humid climate. But field work close to the coast can be a damp nightmare; thrashing through the dense vegetation, bathed in sweat in the summer or getting rained on in the winter. Either way you get wet. At higher elevations pine forests take over and higher still, there are the alpine meadows that serve as summer pasture for sheep and goats. It’s so beautiful up there that I often found myself tapping on rocks with a hammer but hoping we wouldn’t discover a mineral deposit to mine.

Who Let The Dogs Out?

A rural Turkish family might own a small stone hut or rough timber cabin up in their traditional yaylas -the summer alpine pasture. Their kids head up there alone for a few days at a time armed with a bag full of hard cheese, some flat bread (lavash) and a container of fresh yoghurt, shepherding small flocks of smelly sheep and goats. We often ran in to lonely looking kids, tanned and dirty, perched on the rocks watching as their goats and sheep did what they do best: eat, shit and go baa. The flocks are protected by huge white Kangal dogs- vicious rabid monsters singularly focused on protecting the animals in their care -that wear bondage collars studded with outward facing nails to protect their throats from wolf or bear attacks. You do NOT fuck with them; anything daft enough to attack a bloody Kangal deserves what it gets if you ask me.

After a 2-day drive from Ankara to Trabzon, Marlborough Man and I began to work our way south along one of the many small mountain roads that climb up toward the Pontide watershed. Eventually we turned off, parking up in a small village of steep-roofed wooden houses. President Assad climbed out and announced through clouds of cigarette smoke that we were walking from here. Ahead, our path lay upward along a steep, rugged forest road that was still partly buried in snow drifts.

Avalanche Zone.

Off we went, onwards and upwards, hammers in hand, sample bags at the ready, but after a couple of kilometres our path was blocked by a mountain stream that had cut its way through a thick chaotic jumble of hard-packed snow, tree trunks and boulders brought down by the spring avalanches. We were aiming for a feature a mile or two up ahead that had been tagged by our satellite image-processing, so we had to get across the stream somewhere. We chose a likely spot and gingerly picked our way over the boulders to other side, prodding the snowbank with sticks to make sure it was stable. On the far bank we found bear footprints in the snow. Fresh ones and bloody big ones with it, which didn’t bode well so we kept our eyes and ears open as we walked.

Our Work Here Is Done.

A few hours later, professionally speaking the day was a bust. We’d prospected above the tree line and had found nada, so we decided to turn back before it got too dark for the drive back. The President had burned through another 20 butts and had just about run out, so he was beginning to panic as nicotine deprivation (it’s a relative term) kicked in. We had a couple of hours walking to get back to the truck and an hour or two of driving so it was time to go.

The tactical retreat went according to plan until we got back to our stream crossing, which was now a raging torrent of ice-cold water and boulders. Our snowbank had gone. We’d made the rookie error of crossing a stream in the cool of the morning before the heat of the day kicked in and the snow melt started. This was a serious problem. If we couldn’t cross, we’d be stuck overnight above 9,000ft in bear country with no tent, no sleeping bags and the very real danger of hypothermia.

Hi There, I’m Stupid.

We scouted up and down the stream and eventually found a spot where there were enough large boulders that we could use to cross and I volunteered to go first – rookie error #2.

I threw my pack across to the far bank and stepped carefully on to the first boulder and then the second one, but as I put my weight on it it shifted and rolled, taking me with it. My legs slipped off and I dropped backwards on to the boulder which continued to roll pinning my left leg at the shin against the rock I’d been aiming for. I was stuck, trapped by one leg, perched slightly above the surface of the fast-running stream, lying prone on a dodgy boulder.

Undeterred, President Assad sprung into action, a lit cigarette clenched heroically between his lips. He stepped nimbly over me on to the last boulder by the far bank. Meanwhile, I levered my self upright up and reached out a hand to Mehmet who’d sat down on his rock and was using his legs to push on my boulder, attempting to shift it. He shoved harder, with me pulling on his hand to pull myself upright, and my rock moved just enough for me to get my leg free, but now that I was free I dropped forward between the 2 rocks into waist deep icy water. Gasping with the cold, I scrambled as fast as I could around Mehmet’s perch and grabbed a fist full of grass on the stream bank, pulling myself up just as the 2 boulders came back together with a loud clunk right where I’d been standing.

I was soaked, sporting nice bruise on my shin, but I was also counting my blessings that it hadn’t turned out worse. A bit too close for comfort but my dictatorial friend had saved the day. I was also pissed-off at what a daft twat I’d been crossing the stream when it should’ve been obvious that the water level would come up during the day. Lesson learned. The moral of the story? Other than me being an idiot, I really can’t think of one.

And remember…

I did live to tell the tell, despite being really bloody stupid in the early days of my field career. If you’d like more instalments of stupid, please subscribe using the stupidly small subscription box at the top of this page. Reading my stuff is guaranteed to make you feel a whole lot cleverer than me. Which isn’t hard.

Adventures with the adventerous Ralph….so much fun!

I can hear the river and smell the cigarette smoke…and memories of my own stupid stunts and bear prints flood in. Thanks for triggers and the giggles.

KEEP on writing. cheers!

Yet another great tale Ralph. Its amazing you’ve lived to be as old as you are.