Blowin’ In The Wind

(click above..you won’t be sorry)

One of my bestest favouritest rocks is a ventifact (pictured below). It sat on my office desk in downtown Vancouver for the last 4 years and was terribly neglected during lock down, so I brought it home last week to make it feel loved again. It now sits under my computer screen next to a 1kg cube of tungsten metal and a small brass cock. (As an aside, the tungsten cube is unbelievably dense – the same specific gravity as gold at about 19.2).

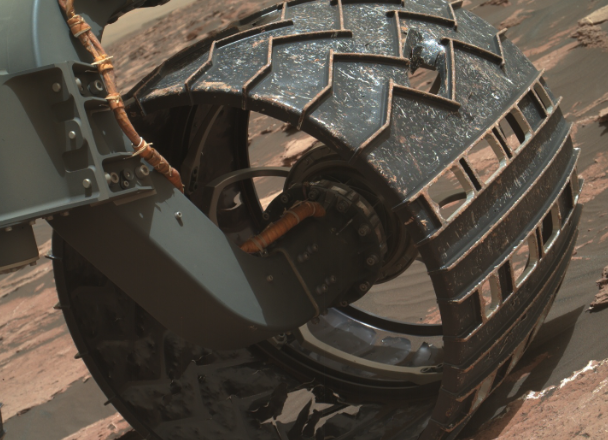

Ventifacts are naturally polished rocks that have been shaped by wind-blown sand or ice, typically in desert environments -a process known as as “corrasion“; a new technical word for me, which just goes to show you’re never too dumb or too old to learn. They’re found in deserts all over the world from Antarctica to Egypt and have even been recognised on Mars where they’re suspected to have damaged a wheel on NASA’s Curiosity Rover. The term -which loosely translated from the Latin means something made by the wind- first appears in the literature around 1911; a British geologist coined it to describe wind-shaped rocks he saw in Africa and parts of Asia.

The longer ventifacts are sandblasted the more regular shaped they can become. The windblown particles etch out a flat face along the side that faces into the prevailing wind direction. If the average wind direction shifts -or if the pebble shifts- the wind starts to facet a new face. Ventifacts that develop 3 sides, like small triangular pyramids, are known as Dreikanters (3-sided in German.) If they have 2 faces, they’re known as Zweikanters. They also develop sharp ridges -which caused the Rover damage- and grooved surfaces which are used to infer paleo wind directions assuming the ventifacts are found in situ.

My Precious

I found my ventifact about 25 years ago in Baluchistan in western Pakistan, at the site of an old onyx quarry while I was prospecting with my perma-cheerful Pakistani geo-colleague, Naseem (See pic). It’s a prismatic Zweikanter, sand-polished to a beguiling translucent sugary white colour, that fits my hand perfectly. When I found it – I saw it from 50m away- it was lying on a cobbled surface of jet black, desert-varnished rocks. I trousered it and spent the rest of the trip with one hand in my pocket rubbing my lovely new rock which didn’t go unnoticed by my increasingly worried government security team.

It’s Old.

Pakistan wasn’t the first place I saw wind-shaped rocks. I’ve seen them in southern Africa in the Namib desert, and on the Arabian peninsula in Yemen as well. I’ve also found some seriously ancient ones, clocking in at over 2.7 billion years old, underground in the gold-bearing conglomerates of the Witwatersrand basin in South Africa.

The Wits mines exploit ancient gold-bearing gravels that filled a huge sedimentary basin. The basin was big, possibly 300km or more along its long axis and huge fan deltas formed where rivers flowed into it. There’s been a lot of debate amongst academics about the origin of the gold in the Wits. Is it detrital? Hydrothermal? A hybrid of the two – remobilised detrital gold perhaps? What isn’t in doubt is the association of gold and pyrite with sedimentary rocks – metamorphosed sandstones and conglomerates- and carbon and uranium. Underground, in the active mining faces, you can see incredible cross-bedding structures in the conglomerates with detrital pyrite tumbling down the cross-bedding planes in fossilised river gravel bars.

Slack-Jawed Idiot

It was in one of these that I found a Dreikanter while I was mapping a face one morning; a quartz pebble about an inch long, with 3 perfect faceted sides at about 120 degrees to each other. When I saw it, I stopped mapping and stared at the face for a couple of minutes in amazement before gently loosening it and sticking it in my coverall pocket (I lost it years back sadly.)

Being a moderately erudite fellow, I’d read about ventifacts and immediately recognised what it was. We’d also covered them (briefly) in our interminably dull sedimentology classes at college, although I’d never seen one in the flesh; but there it was, real as can be, a textbook perfect Dreikanter sticking out of the rock face. It was largely undeformed despite being close to 3-billion years old (unlike me; at a mere 60 years old I’m starting to show definite enlargement along the x-axis.)

There have been a few moments in my career when some geological feature or other has made me stop and stare like a slack-jawed idiot. It usually happens when I see something on a grand scale, like the fold and thrust geology of the front ranges of the Rocky Mountains near Banff in western Canada, or walking along the mid-ocean spreading ridge on Iceland. Another memorable occasion was driving past a sky-blue mountainside in northern Iran, coloured by high concentrations of the mineral dumortierite. But here I was, 7,000 feet down, drenched in sweat, staring at the face like a teenage boy with his first grubby centrefold.

It’s Just a Pebble

My underground assistant had noticed that I’d hit the pause button and came down the face to check up on me, making sure it wasn’t heatstroke kicking in. He was a bit non-plussed when I pointed out the tiny pebble that had caught my eye. What I wanted to tell him was that it was irrefutable evidence that we were staring at the actual surface of our fair planet from 2.7-billion years years ago. Heady stuff, but my Fanakalo – the mineworkers’ pidgin Zulu – didn’t stretch to lectures on sedimentology. What came out was “Please pass me the water bottle and my hammer.”

Bear in mind I was only 22 years old and easily impressed – a cheap date in geological terms – but even so, this was mind blowing. My little triangular pebble was being shaped by sand at a time when the Earth’s atmosphere was being oxygenated by cyanobacteria; a small part of a giant sheet of gravel tens of miles across where streams and rivers meandered back and forth. It lay there without a worry in the world as the life forms that had thrived in the old anaerobic environment passed away, yielding to the evolving oxygen breathers.

Then one day erosion did its thing, and my rock was incorporated into a river bar made of gravel and pyrite which is where it stayed for the next 3-billion years. It survived all sorts of geological brutality while waiting for me to come along -metamorphism, a giant meteorite impact and burial under kilometres of Ventersdorp lavas– but it was still recognizable as a ventifact when I found it.

That was one tough little pebble.

And remember…

The best way to ensure that I post fewer dull geological stories is to subscribe using the small sand-blasted subscription box at the top of this page. Add yourself to the list, then send me lots of snotty emails demanding more humour and less geology. Peer pressure is a powerful thing.