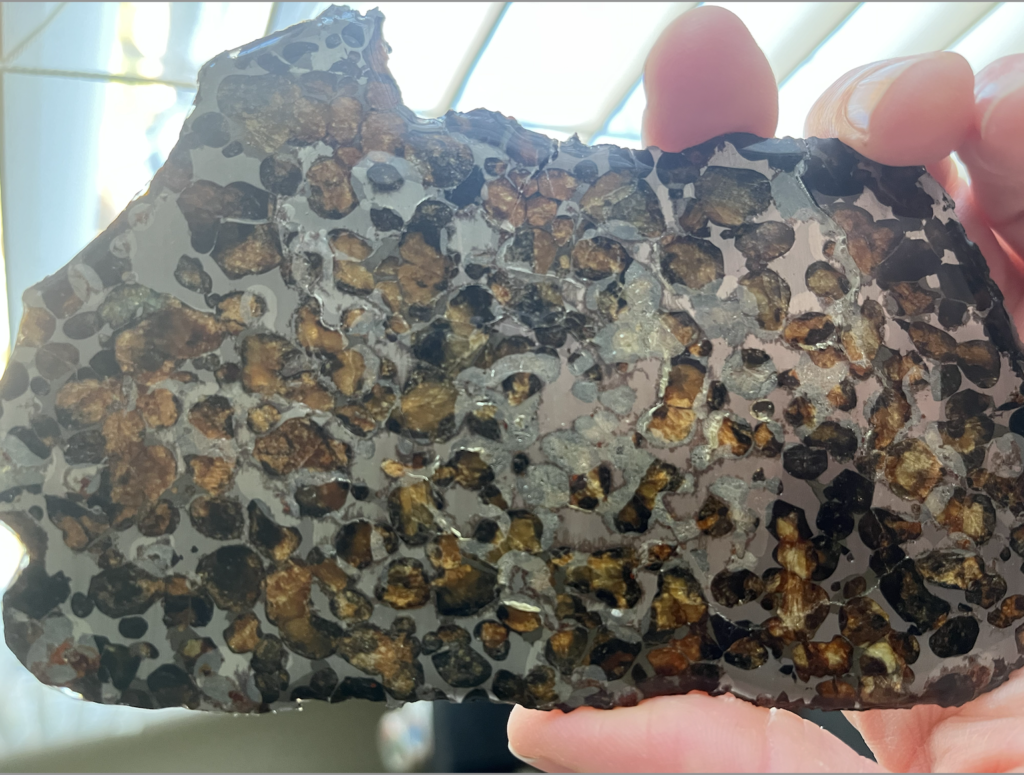

The Campo Del Cielo meteorite.

Life’s little rituals are important. I have one that takes place every March and is something I look forward to in these troubled times we live in. It doesn’t involve weird clothes, funny handshakes or rubber wear but it does involve rocks, money and the Grenville Minerals booth in the trade show at the PDAC conference in Toronto. Over the last 20 years, I’ve become a regular Grenville customer, saving my pennies to buy a couple of new samples for my collection when PDAC comes around. They’re my first port of call on the conference Sunday when the grumpy security guard swings open the trade show door and the unwashed pile in to stare blankly at drill widgets and AI core logging gadgets. They’re not the cheapest, and it’s mainly force of habit that keeps me going back, but to be honest my year isn’t complete without lugging home a small, heavy cardboard box full of bubble wrapped rocks.

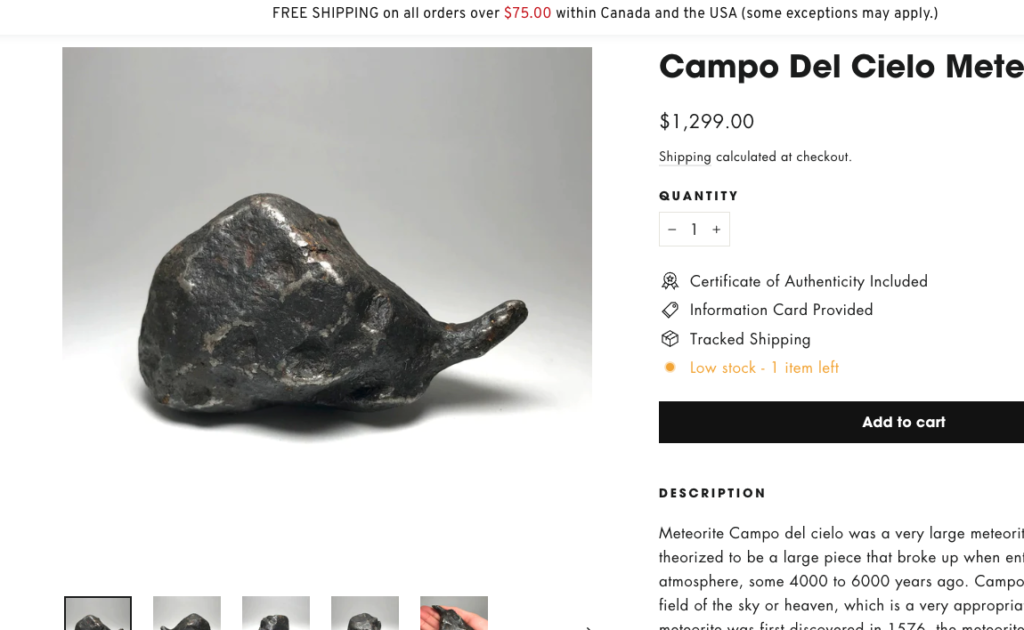

Bloody Hell, Ralph, That’s Expensive

I bought this beauty, a 3lb piece of the famous Argentine Campo Del Cielo (CdC) nickel-iron meteorite fall, a decade ago. It cost me about $500. As I brandished my overworked credit card to pay for it, I chewed over what I was going to tell my skeptical wife when I brought home a dull, black, heavy lump instead of the usual pretty crystals. Even I – a highly persuadable collector- thought $500 was a bit steep for a chunk of iron, albeit one from the outer reaches of the solar system.

It weighs in at exactly 1,600g so I paid 32c a gram for it. Since then, prices have er…. rocketed, and they now start at about US$1 a gram but can go up to $10-20 a gram at auction. Quality 1-5kg stones seem to fetch around $2-4 a gram so with hindsight it was a good investment: given the choice between junior mining stocks or a good space rock I know which I’d buy.

Mr. World Meteorite, 2010

My piece is a great example of what a meteorite should look like. It has a sexy, silky blackened fusion crust, formed when the meteorite slowed down enough to allow the hot melted surface of the rock to cool and re-solidify. It also shows curvaceous ablation pits – the thumb sized hollows on the surface of the stone also known as regmaglypts- which formed as the melted, liquid iron alloy was pulled off the surface of the meteorite as it barrelled through the Earth’s atmosphere. And if I sliced it in half and etched it with nitric acid (perish the thought) it would likely show the classic criss-cross, interlocking Widmanstätten crystal texture found in many nickel iron meteorites.

Swarms Of Them

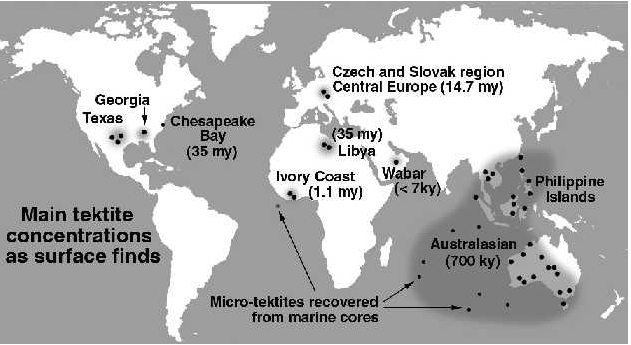

This may seem obvious, but meteorites tend to fall in groups or swarms, or as individual stones. Swarms -where many rocks from the same meteor are found close together- are known as “strewn fields.” Multiple strewn fields have been found around the world, but the Campo Del Cielo field is probably the largest cluster of actual meteorites known. The others are mostly tektite strewn fields.

Tektites are blobs of natural, solidified glass splashed up into the atmosphere by large impacts but there may be nothing left of the actual primary meteorite. For example, if you were unlucky enough to be lost in the Sahara desert of western Egypt or eastern Libya, crawling around dying a slow, pink, sunburned death from dehydration, you could while away your last miserable hours by looking for chunks of distinctive yellow-green melted glass, one of thousands that are scattered over the Great Sand Sea. They’ve been dated at about 29-million years old and were probably formed by a large impact or by a high temperature blast wave associated with an air burst comet or meteorite.

And as you slipped away, face down in the sand covered in dust and flies, with your final thoughts you might ponder why there’s still no known crater associated with the glass. A good question, because estimates suggest that if there once was a crater, it could have been up to 10km wide. A hole that big is hard to miss even in the desert, hence the air burst theory.

Desert glass is bloody expensive stuff too and a bit rich for my blood, selling for about $20 a gram if you buy from a reputable dealer. The Egyptian Pharaoh, Tutankhamun, had a piece of it carved as a pale-yellow scarab beetle, and set in a rather ostentatious space-bling broach that was found on his mummy. Lucky mummy.

Bloody Tektites, They’re Everywhere

A few thousand miles further east, another huge tektite fall covers most of the Indochina peninsula, parts of China, the Micronesian islands and Australia; almost 30% of the Earth’s surface by some estimates. They’re thought to be about 788,000 years old, thrown up by an enormous impact which must have been a hell of a sight for our tree dwelling ancestors as molten blobs of black glass started raining down on them. The tektites are black and rounded, elongate or tear-drop shaped. Again, the impact crater is currently MIA but it’s eroded roots may lie somewhere in modern day Laos or Cambodia, or perhaps deep down in the mud of the Gulf of Tonkin.

It’s Cold

Antarctica is another famous location (in the broadest sense) for meteorites because A) The continent is big, b) Ice sheets are generally white, and c) space rocks are generally black making them easy-ish to find when they’re on the surface. To collect them, teams of intrepid researchers head out for days at a time on skidoos loaded down with gas, canned tuna and toilet paper, scouting for small black lumps where the ice sheet runs up against mountains or ridges. As the flowing ice collides with an obstacle, it’s eroded off by the wind and anything carried along by the ice -such as space rocks- collects at the surface waiting to be found. The last time I delved into the NASA data, roughly 42,000 or so space rocks had been found by teams in Antarctica, but many of these are individual stones and not strewn fields.

But Back To The Main Event

The Campo del Cielo strewn field is unusual in both the number of stones found to date and because 26 craters have been identified, testimony to the violence of the event as the meteor broke up before impact. The strewn field measures about 3 by 19 km but pieces have been found along a 60km path. The fall is about 4,200-4,700 years old based on carbon-dating of charred wood fragments found in the craters and under the bigger stones. This age range meshes with the oral tradition of the local indigenous peoples who tell of things falling from the sky that set the forests alight, and were using the meteoritic iron to make tools and weapons long before Europeans arrived on the scene.

Put That back.

God knows how many CdC rocks have been have been spirited away from the shores of Argentina since the colonial Spanish first found them in 1576 but it’s likely in the thousands; so many in fact that the Argentine government finally banned dealers* from exporting them and now arrest any smugglers they catch. But that doesn’t seem to have stopped mineral dealers from selling them and you can still find plenty to buy online. Beware though, there’s a thriving market in CdC fakes. *Weasley disclaimer time: mine was bought before the ban was put in place and, at the time, I had no idea what the CdC was. I just wanted a space rock.

The official tally of CdC stones is a bit vague but over 100 tonnes of material have been recovered including huge chunks like “Gancedo” at 30.8 tonnes and “El Chaco” which weighs in at 28.8 tonnes. Taken together, the pieces constitute largest known meteorite on earth, with second place going to the Hoba meteorite in Namibia, a mere stripling at 66 tonnes.

What Is It, Exactly?

Meteorite classification is not something I was taught as an undergraduate back in the early 1980s. My extremely simplistic understanding of it is, there are 100% metal ones, 100% rocky ones (rocks with small, rounded things in them are known as chondrites), and a lot of in-between-stony-iron-ones like pallasites. (I own a nice slice of a pallasite from China) The rest either come from Mars or the Moon and are far more valuable than gold if you’re lucky enough to find one, selling for $300-500 per gram. Anything else meteoritic is officially classified as weird.

The 3 main types formed at different levels within one or more large asteroids or small planets that broke up during massive collisions early in the solar system’s history. Nickel-irons are the cores of the bodies, and the stony ones are the outer mantle or crust. The stony-irons originated in the transition between outer silicate-rich layers and the iron-rich cores. CdC is composed of the nickel-iron alloy Kamacite so it’s part of the core of a long-dead planetoid which got smashed to pieces in a celestial mosh-pit billions of years ago, and then ended up on my desk. I think that’s well worth $500.

But What Does It All Mean Metaphysically?

The $500 seems even more of a bargain when you consider the consderable metaphysical benefits that a space rock can bring to our humdrum little lives, something I didn’t consider that chilly March long ago. Meteors spend billions of years orbiting the sun on our behalf, working hard to soak up its energy for us. When they land, we can use that energy to connect our root chakra to the Earth, assuming we have the right cables. And like a portable battery, I can charge Old Spacey any number of ways. If I immerse it in soil over night, I’d be able to meditate with it (to it?) and suck up all that loamy-wormy energy from my by now rusty meteorite. Or I could sing my favourite songs to it and channel its new-found atonal energy to relieve my stress while the neighbors bang on my door and tell me to shut the fuck up with the awful shouting. I have so much to learn.

And remember..

If you like reading blog articles like this one that were forged in fiery collisions in outer space, then you’ve come to the right place. Please take the time to subscribe via the intergalactic portal at the top right of this page cunningly disguised as a subscription box. You are 100% guaranteed to be disappointed. And I just noticed I wrote this entire piece with only 1 swear word – I’m slipping.

Meteorites are cool…….well, not when they are falling, obviously, but you get my drift?

Prefer my specimens of Trinitite !

Cool in an Oppenheimer-ish sort of way !

wow.. you have some trinitite? Send a pic.. would love to see that.

Sent a pic to your email Ralph – feel free to post !

Another really interesting post Ralph, thanks. A meteorite specimen I don’t have.

Hopefully this response will get through. I wasn’t able to respond to your previous couple of gems.

Regards

John

thanks John.. This did get through. Note sure why you others didn’t but then again, I’m a technomoron. Regards..