My New Favourite Hike

An 11-hour walk with 825m of uphill is not everyone’s idea of fun, me included. Don’t get me wrong. I can do it -I’ve walked up to 30km a day on long distance hikes in the UK in recent years, but the UK is a lot flatter than BC and it’s considerably more relaxing because there’s nothing big and snarly that will eat you. So, the unsettling prospect of the day’s climb was nagging away at me as we pulled into the Takakkaw Falls car park, near the town of Field, BC, at 7am on a fine August morning this summer. The lot was empty, darkly waiting for the tour buses and the instagrammers with their perfect outdoor clothes to come and gawp at the falls through their phones.

The Walcott Quarry

My wife had booked a guided day-hike with Parks Canada, up to the famed Walcott Quarry on Mt Field where dark, shaley middle Cambrian-aged sedimentary rocks known as the Burgess Shale are exposed. At $120 a head it’s not cheap, but it’s the only legal way to see the site, which was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in the ’80s. It’s been on my geo-weeny bucket list for a few years now; a legacy of reading Stephen Jay Gould’s popular science classic “Wonderful Life” in the 1990s. Fossils have been mined there for over a 100-years and Gould’s book was instrumental in drawing broader attention to the key role they have in unravelling the early evolution of animal life on Earth (stick the words “Cambrian explosion” into the google-izer and you’ll get enough search results to ensure a good night’s sleep tonight.)

The sedimentary rocks formed on the sea floor off the coast of Laurentia; what we now call North America. This was a sea floor that teemed with newly evolved life; soft bodied worms, sponges, crafty trilobites, nasty predators with gripping claws and radiating teeth, weird unrecognizable multi-legged things, and less weird recognizable molluscs with hard shells. But it’s the presence of fossilised soft body parts that have made the petrified relics a must-see for many paleontologists and evolutionary biologists.

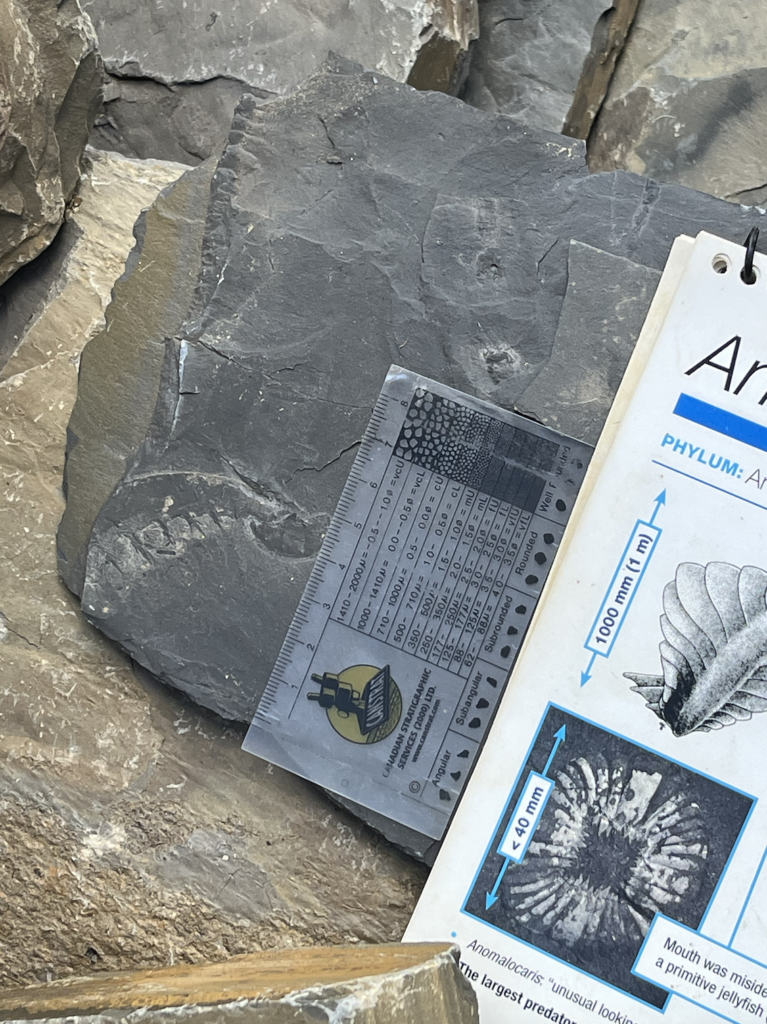

A trilobite – hard body parts. And a squishy thing with soft body parts – definitely more interesting. Really.

Squishy Ooze

In simple terms, the host sediments are thought to have piled up at the base of an ocean-floor cliff that was prone to shedding regular torrents of mud, periodically burying the entire happy little ecosystem in choking sediment. The poor critters that lived there were quickly trapped, killed, flattened and -unusually- their soft body parts were preserved by the fossilization process for modern-day geoscientists to find. Typically, all we’d find of our dear departed Cambrian ancestors are shells and other hard parts, so scientists have had to make educated guesses at the body shape of the original animals. But not so with the Burgess Shale organisms which can be so well preserved as dark, carbon-rich recognizable shapes on bedding planes that the original animal practically jumps out of the rock at you.

Don’t Steal The Fossils

Because of its value to science and the stunning beauty of the alpine location, the site is now closely watched by Parks Canada. Hidden surveillance cameras monitor it, connected to a secret control room where Ninja Death Rangers are on call to exterminate unauthorised visitors about to pillage the quarry for fossils. And fossil theft does happen. If you do the hike, ask the guide about the 2 foreign tourists subtly clad in matching Hawaiian shirts who raided the quarry and ended up jumping into a freezing-cold river to escape the authorities when they were finally tracked down at the Truffle Pig* restaurant in Field.

*A most excellent spot for a cocktail and a good meal!

Two Many Geos

After a quick intro’ by the guide, and a short lecture on the ground rules- “be safe and don’t nick the fossils” -we set off toward a steep zig-zag route that screamed thigh pain up / knee pain down. Our intrepid group was small. A half dozen folk kitted out with day packs, walking poles and light weight boots gathered by the ranger’s car. My wife was convinced that everyone was fitter and better equipped than us, but we needn’t have worried; the pace is reasonable with regular water and rest breaks.

Up we went, heads down, sweating, as we negotiated a couple of dozen switch backs up the first 300m of vertical ascent to the Yoho Lake camp site. There we picked up another half dozen walkers who were camping at the lake, including another geologist -a final year undergraduate from Carlton University who was way more up to date on his paleontology courses than me (the last one I took was in 1983). I was thrilled to have another geo on the trip. It meant I wouldn’t be the only one boring the nuts off the rest of the group with incessant, dull rock talk.

My My It’s Spectacular!

To call this hike spectacular would be to do it a disservice. Once you’ve cleared the forest path at the top of the initial ascent, the route emerges onto a west-southwest-facing slope looking over Emerald Lake. From there, the glorious views come thick and fast and the long walk to the quarry passes incredibly quickly. The weather cooperated too. It was a perfect twenty degrees or so warm with a few scattered clouds to give us regular breaks from the sun as we traversed across the open alpine slopes.

But It’s A Slog

The hard final ascent to the workings follows a series of ever-steeper switch backs leading up a scree slope to a small man-made quarry cut into the sharp, horizontally bedded, slatey Cambrian rocks. A large metal lock box sits near the entrance. Our guide opened it up and pulled out hard hats, enormous hand lenses and weather-proofed fossil guides for all of us. The site rules were simple. Don’t climb the walls; don’t keep any fossils unless you want to be arrested; don’t throw rocks around and leave nothing behind.

There’s Tons Of the Buggers

Happily, the fossils aren’t hard to find. In fact, there are loads of them, particularly trilobites, branching sponges and small limpet-like molluscs that look like little flattened cone-shaped hats. Funny enough, the best finds are clustered around the strong box where previous visitors had left them. Any fossils we might pick up that looked particularly interesting would be stashed in the lock box with a written record of where they were found and by who, so the academic types could review them at the end of the season for any actual scientific merit.

We had about 2 hours to ourselves in the diggings, and there was a quiet but excited buzz in our group as we stumbled about picking up sharp slabs of rock (you’ll end up with nicks and small cuts on your hands from the pieces of sharp shale.) I was so excited to be there that it felt like my first ever undergraduate geology field trip. The only thing lacking was a realio-trulio paleontologist as a science guide, but our tour guide knew enough to keep the group happy. Me and the other geologist were happy as 2 very fat pigs rolling in a lot of shit and every new find was greeted with whoops and some excited chatter.

It’s A Prawn! It’s A Jellyfish! No It’s Anomalocaris!

My day was made totally complete toward the end of our allotted time in the quarry when I glanced down at my well-worn boots and noticed to my delight that I was standing on a largely complete frontal appendage of the apex predator of the time, Anomalocaris. My fossil was about 2-3 inches long and seemed to be holding something – a tasty animal victim perhaps, so I took it to our guide, who thought it was interesting enough that the scientists might want to see it at the end of the season. She had me fill in a form (name and age[!] but no address) and it was stashed away in the lock box awaiting collection when the professional academics turn up in their helicopter at the end of the season.

Anomalocaris was about 30-40cm long and swam about in the Cambrian waters dealing carnivorous death-from-above to the seafloor bugs. After death, it was apparently prone to falling apart and the early workers conjured up no fewer than 3 different beasts from its remains. The barbed appendage I found was described 100 years ago as a fossil shrimp -an understandable error given that they’re curved and look to have legs- but it’s more akin to one of the grasping front limbs of a praying mantis. Similarly, the animal’s rounded mouth parts were first found separately and described as a species of fossil jelly fish. The youtube video linked below (hopefully) shows a fun reconstruction of Anomalocaris endangering a trilobite.

It’s All Down Hill From There

After that it was all down hill, literally. We retraced the 11km walk in and got back to the now busy car park at about 6.30pm. We’d seen nothing in the way of large wild animals all day except for a single obese marmot hanging about at one regular stop, and a curious pika that licked the salt off our back packs at the lunch stop. The guide had regaled us with tales of herds of mountain goat hanging about the quarry, but they obviously missed the memo and had buggered off when we visited.

My over riding impression of the site was one of amazement, in part for the sheer scientific wonder of what I’d just seen, but also at the persistence of Charles Walcott, the geologist and fossil hunter who found the site in 1909. He was drawn to the site “after labourers working in the nearby village of Field told McConnell about “stone bugs” (trilobites) they had seen on the slopes of Mount Stephen“. In the late 1880s, Walcott worked on a couple of specimens that were sent to him by a colleague and decided that they were probably middle Cambrian in age.

In 1907 he finally got to visit the trilobite beds discovery in person, and a couple of years later, on a return trip, while traversing the western slopes of Mount Field alone on horse back he was lucky enough to stumble on the first Burgess Shale fossils and subsequently spent 5 days that September collecting fossils with his family.

For what it’s worth, my family would never spend 5 days bashing rocks with me on a remote hillside without bribery or heavy sedation, but the Walcott’s enjoyed it so much, they went back there year after year building a world class collection of Burgess fossils. Since Walcott’s day, the site has been studied by such august institutions as the Smithsonian, Harvard University and the Royal Ontario Museum so my modest little find is in good company. Anyways, if you get the chance to do the hike, take it. You won’t regret it and if you’re lucky, you may well add to our knowledge of the site.

And remember…

It’s been a while since I last posted on the blog. A touch of writer’s block, mixed with a hint of laziness and a temporary absence of stories meant that you, dear reader, got a break from my dull, badly written memories. If you’d like me to take a longer break, you can send me money and I promise not to write anything so long as the cheques keep rolling in. If you like what I write, please subscribe using the fossilized Cambrian-era subscription box at the top of this page.