In the mid-1990s I spent the best of a year in the province of West Azerbaijan in northern Iran, based in the small farming town of Takab. The area, about a day’s drive from Tehran, is populated largely by Turkic and Kurdish people and Zoroastrianism is still practiced there. The day-to-day language is Turkish. Rural and fairly remote, life for the villagers goes on as it has for thousands of years.

I was running an exploration program at a project called Zarshuran (“the place of the gold washing”) working a 6 weeks in / 2 weeks out rotation with Budapest as my home base.

The routine in Iran was pretty simple. Get up. Eat breakfast: flatbread with honey, eggs and yoghurt. Spend the day at the project. Come back to the Hotel Ranji in Takab. Eat dinner: chicken or beef kebab, yoghurt and grilled tomato. Sleep. Repeat for 6 weeks.

One day in 1996 or ‘97 my daily routine was pleasantly interrupted when a Dutch traveller turned up at the hotel. In Iran for his friend’s wedding, he was on his way to visit an archeological site near Takab: Tahkt –e Soleyman (the name means Prison of Solomon and legend holds that King Solomon used to imprison monsters there.)

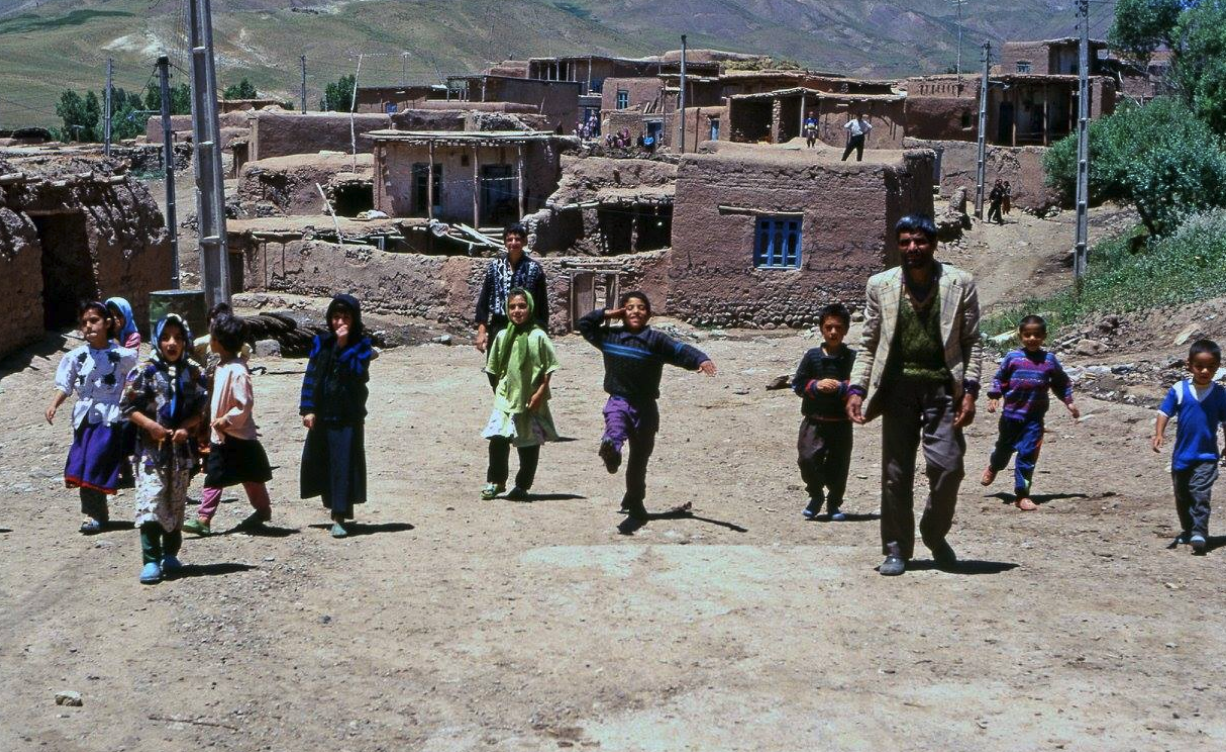

In need of English-speaking company, I persuaded him to travel to my project for the day. It was a 45 minute drive from Takab through small farming villages where he got a chance meet the locals and photograph the hard-scrabble life of Iranian subsistence farmers. As a bonus, I took him underground at a small but spectacular arsenic mine to collect world-class samples of bright yellow orpiment (arsenic sulphide) from the ore pile.

Twenty years later, out of the blue, I got an email from him. He’d tracked me down on-line using an old business card I’d given him during his visit. And attached were 20 scanned photos from his day on the project which he said was the highlight of his trip to Iran. I was totally blown away. All the photos I’d taken at the project were of rocks, drills, and general technical stuff with a few scenery snaps thrown in. But here were photos of me, at 33 years old, looking vaguely like a geologist on a day I’d long since forgotten about… being all earth sciencey and authoritative at the Zarshuran project, which is now Iran’s biggest gold mine.