In a departure from the usual mining-related sarcastic drivel, here is a short story about my mother’s dim and distant origins -and hence mine too- which are rooted in one of the key historical events of the 20th Century; the onset of World War 2. Anyone raised in Europe, with parents or grandparents in their 80s who are still alive, has a link to the war because directly or indirectly, it affected everybody on the continent.

I should note that this is a very superficial backward glance at a critical period in European history. I deliberately make no judgements on the horrific events of that period -my aim in writing this down was simply to document the family’s experiences for my 2 sons while I still have access to real memories from the time. To be fair, my mum was very small – only 6 when the war ended and 7 when the family was deported- so the stories are patchy and remembered through the eyes of a child but enriched with details gleaned from her parents and historical archives available on the internet.

Out Of Graslitz / Kraslice

For most of my adult life I’ve been aware that my mother’s roots are German-Czech, and that the family ended up in Germany in 1946 but some of the detail was lacking (for me at least.) She was born in 1939, a tiny hamlet called Silberbach on the outskirts of a small town called Graslitz in the far west of Czechoslovakia, 5km from the German border. Now known as Kraslice, it’s nestled in wooded hills and valleys; the town name may derive from the medieval German word “Graz”, a pine forest, which fits the countryside, but it may also mean small castle. The family were affluent ethnic Germans, with a thriving business making lace and musical instruments.

In 1930, Graslitz had a population of about 13,000. It suffered during the post-war communist period as socialist-brutalist architecture replaced the traditional Germanic buildings, but enough of the old town remains to hint at its former beauty. The old family residence and the factory still stand on the outskirts of Graslitz, albeit converted into modern apartments. A shop-cum-showroom in the very centre of Vienna, decorated with the family name Breinl, also survived the war.

The Sudetendeutsch

The western border region was part of the Sudetenland, named after the Sudeten mountains, the highest part of the Bohemian massif that stretches along the northern Czech border into today’s Poland. German speaking people known as Sudetendeutsche formed the majority of the population. They spoke a broad German dialect, Sudetendeutsch, which I grew up listening to in my grandparent’s house when we visited. Reluctant Czechs, they found themselves on the Slavic side of the border after the Austro-Hungarian empire was broken up. Mostly catholic, they numbered close to 3-million people -a quarter of the Czech population- but their cultural ties were more aligned with their fellow Germans across the border.

With their Catholic beliefs, it wasn’t uncommon for families to have up to 10 or more children. My grandfather was one of 10 children – 6 daughters and 4 sons- and his family shared their enormous house with his uncle upstairs who had another 12 offspring. So, I’m distantly related to the descendants of their combined progeny of 22 brothers, sisters and cousins -all with my grandfather’s family name Kohlert- many of whom ended up in Austria.

A few years ago, I was attending a Breinl family reunion in Graz in southern Austria and grabbed the chance to visit Graslitz. I drove my mother and my eldest son across Austria to the Czech Republic, stopping along the way in Prague, Pilsen and Karlovy Vary to sink a few fine beers. We saw the family house where mum was born and visited the local graveyard -a very German pastime- which contains dozens of headstones, all dating from before 1945, bearing the ancestral family names: mostly Breinl on my grandmother’s side, and Kohlert on my grandfather’s.

The Dogs Of War

Fast forward to earlier this year, and the family links to the traumas of WW2 kept nagging at me, prompting me to (finally) delve deeper into our family’s experience of the war.

In 1938 Hitler was becoming increasingly bellicose and the dogs of war were starting to growl happily across mainland Europe. His authoritarian government was calling for the return of the ethnic Germans in the Sudetenland to the German fold. He’d already annexed Austria in March of that year in the “friendly” invasion known as the Anschluss, and the ethnic German lands of Czechoslovakia were up next in his sights. He shrewdly exploited the cultural rift between the German and Czech peoples which began to form in the late 19th century, gathering pace as the region was sucked into his racist agenda. The Czechs were powerless to stop him and by September 30, 1938, it was all over.

Occupation

The previous day, September 29, at a meeting with Hitler and Benito Mussolini, the British government under the appeaser Chamberlain, acceded to Hitler’s demands to annex the Sudetenland. A few hours later, Chamberlain, stepping off the plane onto the runway at Heston near London, waved a copy of the signed agreement and uttered his infamous words “I have returned from Germany with peace for our time”. The fate of the Sudetenland was sealed. On October 1, the German army of occupation moved in to claim the Sudetenland for the Fatherland. Less than a year later, Britain was at war with Germany for the second time in 25 years.

Years back, when my mother was 50, she paid a visited to her aging mother in Germany. They were looking through some old photos in a box when my grandmother pulled out a picture of Adolf Hitler: a typical shot of him standing in his open top Mercedes, surrounded by adoring Germans. But this was different. It was taken in Graslitz on October 4th and my grandparents were somewhere in the crowd. The German population turned out en masse, standing on the sidewalks and leaning out of their windows waving flags, eagerly hoping to catch the eye of the man who had saved them from the ignominy of being Czech.

A German Party

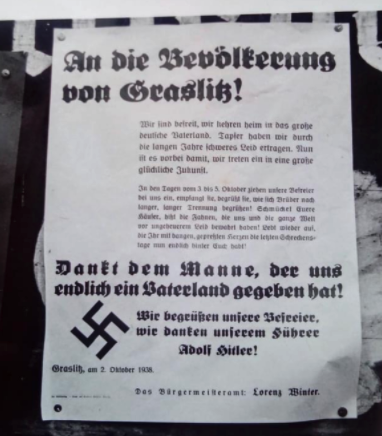

The photo below is of an old leaflet, published that day, from the good folk of Graslitz thanking the German people for bringing them back into the Fatherland. It reads:

“To the people of Graslitz! We are free, we are going home into the Reich. We endured many years of suffering. Now it’s over and we enter a great and happy future. Our Saviours will arrive on 3rd to 5th October. Receive them, greet them, greet them like brothers and sisters after a long separation. Decorate your houses, put out the flags for those who saved us from untold suffering. Live again, you who have lived through long days of terror and can now put it behind you. Thank the man who has given us back our Fatherland. We greet our freedom fighters! We thank our Führer! ADOLF HITLER Graslitz, 2nd October 1938 Der Bürgermeister Lorenz Winter.”

But my grandma had another story to accompany the photograph. The night of October 1, once German forces had actually moved into the Sudetenland, the German population celebrated, drinking a shit ton of schnapps. They got drunk, and -as happens with young couples- the blood pressure went up and my grandparents did what young people in love always do when they drink. Yes, October 1, 1938 was the night my mother was conceived, which is my direct link to a single moment that changed the history of the world. Children conceived around that time became known as Freiheits Kinder -Freedom Children.

She was born almost exactly 9 months later on June 30, 1939 and – as per the wishes of the ruling party- she was given a good German name, Ilse. Some years back, on a camping trip to Europe, my mother ran into a fellow countryman almost exactly her age, who had the same story to tell. He also had a fine German name, Adolf, which -funnily- didn’t age too well.

Deportation

In late 1945, at the end of the war, there was broad agreement between the Allies and the Soviets that the ethnic German population of the Sudetenland should be expelled -ethnically cleansed as we say today- to make room for the Czech people, an ironic twist on Hitler’s concept of Lebensraum. More than 75% of the population of the Graslitz region identified as German and in early 1946, the forced deportations began. Families were moved into Germany on cattle cars with an allowance of 50kg of luggage per person. Many were robbed of their most valuable possessions during the expulsions. Over 1.3-million German speaking people, including my grandparents and their 2 young children, were uprooted from Czechoslovakia.

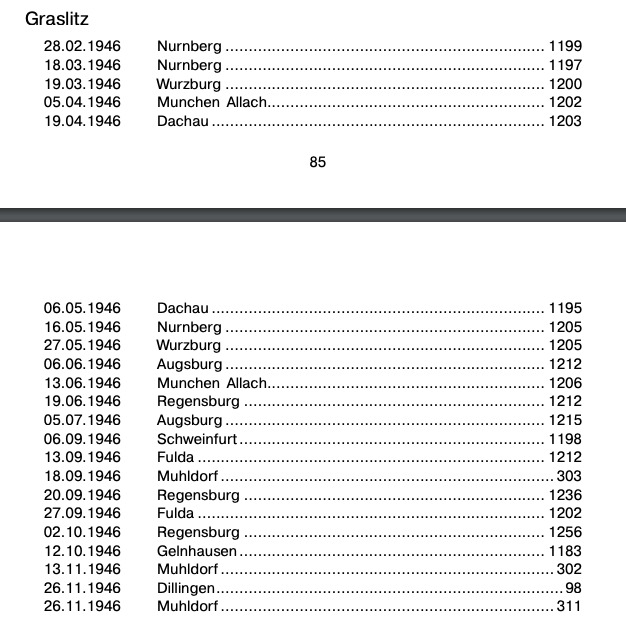

The historical deportation records still exist. Twenty-two rail transports departed Graslitz for Germany during 1946. They moved 22,750 ethnic Germans – about 1,200 per train. As the German population of Graslitz was only 13,000, it’s obvious that the surrounding countryside was also cleared of Germans.

My mother’s family fared a little better than most during the deportations. One of her uncles had served as a doctor on the Russian front and on his miraculous return from the charnel house of Stalingrad he became the only doctor in Graslitz. The Czechs needed him, and his usefulness protected the family to some extent. It may also explain why they were deported so late in the year.

Don’t Forget To Make The Beds

My family was expelled on September 13, 1946 on a train headed to the town of Fulda in the dead centre of Germany. Two or three days before deportation, they had to leave their house clean and tidy with the beds made for the incoming Czechs. They were then billeted temporarily in a dirty cottage within the perimeter of a bigger camp consisting mainly of wooden huts. My mum remembers that sanitation was almost non-existent, so my grandmother had to go back to their home to retrieve a blue enamel potty with flowers painted on it.

Then, a few weeks ago, my brother told me that he still had my grandfather’s luggage trunk, stencilled with his name -Heribert Kohlert- and the deportation wagon number 22. My mum, who was seven years old when they were shipped out, still has her case too, also marked Wagon 22.

Three days and 200 miles later -70 miles a day or barely above walking pace- they ended up in the town of Wolfhagen near the city of Kassel. The train’s snail pace gives a sense of how bad the damage to Germany’s infrastructure was in 1946. It’s hard to fathom what it must have been like at 7 years old, crossing the ruins of a strange country in a cattle wagon. But despite losing everything, the inhabitants of Wagon 22 considered themselves lucky that they ended up in the British Zone and not the Russian zone, which was the next stop along for the train.

You’re Not Wanted

In Wolfhagen the refugees were loaded into a truck and taken to nearby Altenhasungen, a small village of 600 souls at the end of the world. They were dumped in the village dance hall and slept on straw bales for the first night. The next day they were allocated a room -one room for the family of 4- on a nearby farm. But the owner of the farm didn’t want them, like everyone else in the west at that time. The average German was struggling to simply survive in the ruins of the country and the last thing they needed was more mouths to feed. Despite the initial hostility, my mother ended up firm friends with the owner’s granddaughter and they’re still in touch today.

Many thousands of Germans died in Czechoslovakia during the deportations; massacres, individual acts of retribution, starvation and sickness killed an estimated 15,000-16,000 people in the border regions, but sympathy to their suffering was lacking for obvious reasons. In fact, there was a Czech law known as the Benes decree which essentially declared as legal any activities carried out “[whose] objective was to contribute to the fight for regaining of freedom of Czechs and Slovaks or were aimed at righteous retaliation for deeds of occupants or their collaborators” so the partisans, police and soldiers could do whatever they liked to the deportees with impunity and many literally got away with murder. The law was widely hated by the ethnic Germans and even though it’s not been used for well over 4 decades, it has never been repealed.

A Postscript

In a postscript to the story of wartime Graslitz, my mother told me another story which, to a young child, seemed magical at the time but was evidence of a truly horrific episode in the story of the war within the German borders.

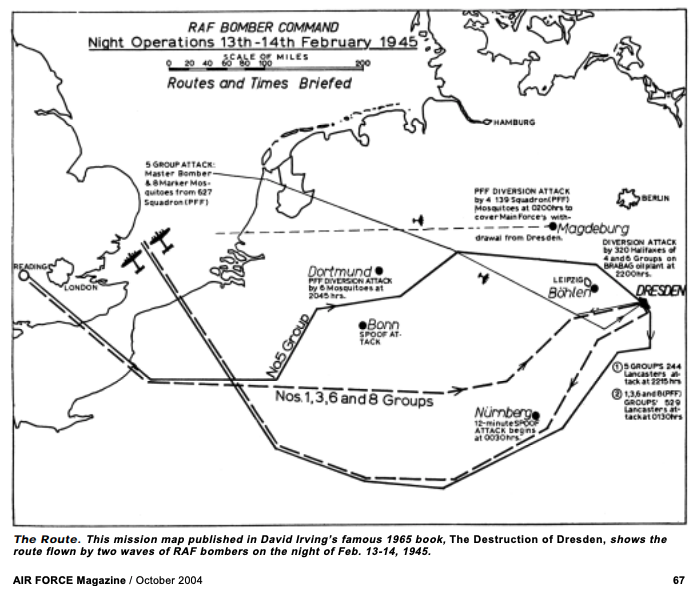

In February 1945, the Allied air force was operating unchallenged over the cities of Germany. Two cities were targeted close to Graslitz: Dresden and Chemnitz. Graslitz lay directly beneath the flight path of some of the bomber squadrons that hit both cities. One of my mum’s earliest memories is hearing the sounds of bombing coming from the direction of Chemnitz, some 70-80km to the north. The Dresden fire bombings, Bomber Harris’ notorious 3-day raid-too-far, marked a turning point in British and American public opinion on the military necessity of the deliberate destruction of city after city. An estimated 40,000 died in the fires between February 13 to 15th, 1945.

One cold February morning that year, she looked out of her bedroom window to see all of the trees sparkling, draped with silver tinsel. Strips of glittery metallic foil hung everywhere. My mum thought Christmas had returned early. It wasn’t until years later that she realised the strips weren’t festive; it was chaff – thousands and thousands of small paper strips coated with aluminum foil that were dropped by the allied bombers to confuse and blind the German radar and their radar controlled anti aircraft guns. She has no idea if the planes were en route to or from Dresden or Chemnitz.

Remember…

If you found this interesting, tough, because I usually write about mining industry stuff. But go ahead and please subscribe using the subscription box at the top of the page.

Fascinating Ralph, thanks for sharing. I wasn’t aware of the forced deportations in 46. G ‘re many was in such a fragile state then it must have been terrible. How about chapter 2 some time, how your mother got to England?

had a response from an old school friend who told me her dad was a navigator on the Chemnitz run.

Another world we forgot at our peril – my uncle was a 16yr old in Berlin when the Russians captured it.

He spent the next 3 years as a POW in Kazakhstan building dams. The prisoners supplimented their diet by eating snakes

He was only released as he faked being mad by way sand, and after a year of that they sent him home !

true & the memories are in danger of disappearing. I was blown away that i could find the actual train departure records from 1946. Gotta love bureaucrats whatever their flavour.

Brilliantly written memories of a small girl in a momentous time in Europe. Thank you.

Very interesting! (Just as interesting as your mining and exploration experiences.) A story like this reminds us of the very tough times that our parents and grandparents often had – and we complain about having to stay home and meet with Zoom and watch Netflix…

While I find the geo-yarns highly entertaining, there is a more personal aspect of your family history to which I can relate, and perhaps should try and document, since I am of your Mother’s generation, and one of my earliest memories is of the same traumatic event to which your Mum referred – only from the perspective of my home at the time – Prague.

it’s always interesting to try to write this stuff down. I held off writing it because I wasn’t sure I could do it justice but I was pleased in the end. And I learned a lot, which was an added bonus.