This slightly sarcastic piece was massively improved by contributions from 4 colleagues: -Brent, Owen, Neil & Mike- all of whom I’ve been lucky enough to know for years. Thanks chaps. You’ll be able to spot where I’ve used your stuff.

Optimist. noun

- a person who tends to be hopeful and confident about the future or the success of something. “only an eternal optimist could expect success”

Bananas

A bit like a 99-year-old man with heart failure buying green bananas, exploration geologists are optimists. We have to be. A bad case of pessimism would be a huge impediment to building a geological career that survives past the initial 5-minute interview with the VP Exploration.

“Can I have a job please? I don’t think we’ll ever find anything, but I’ll give it a go if you pay me.”

“WTF? No. No. No. Who let you in? Piss off. I don’t need a depressed hat stand on my team. Please don’t slam the door.”

A wellness website I picked at random for its daft name, has this to say about optimism. “(it) is a mental attitude characterized by hope and confidence in success and a positive future. Optimists … expect good things to happen….. Optimistic attitudes are linked to a number of benefits, including better coping skills, lower stress levels, better physical health, and higher persistence when pursuing goals.” To which I’d add “poverty” if your optimism is directed at the junior mining sector, although strictly speaking that’s not really a benefit.

Optimism in the junior mining sector comes in many different flavours, from the plucky perma-cheerful investor relations professional -the ones with a fixed whiter-than-white smile as all around them turns to market shitness- to the self-proclaimed geological genius building the next great model of mineral deposit formation based on gut, tea leaves and thumb sucking. They’ve all convinced themselves that everything’s going to be just great for investors so stick with them. Please.

It’s Egregious, Whatever That Means.

IR and marketing people are perhaps guilty of the most egregious levels of optimism in our business. When did you ever meet one at a conference who was negative or down on the company? Shit drill results? “Don’t worry. The hole we’re drilling now is a scorcher, but you didn’t hear that from me.” Flooded mine? “‘Tis but a trickle. We’re buying more pumps. They’ll be there Monday, sucking up that water like beer.” When it’s really going badly they’ll tell you in hushed tones to double down because adding more shit to your existing pile of shit is sure to end well, as we all know.

But I digress. The truth of the matter is, geologists have to be optimistic because nearly all of of us spend the bulk of our careers NOT finding anything -in my case close to 30 years in exploration, sadly without involvement in a world class discovery. Most of us will be involved in smaller discoveries; half a million ounces of gold here or 10-million ounces of silver there, but deep down we all want to find the Big Kahuna and be loved and envied by our poorer, luckless peers. As one buy-side friend wrote to me: “Our whole sector is driven by optimism. Exploration geologists are the extraverted cowboys who only need to make a correct call ONCE in their career to be regarded (by peers and investors) as a hero.”

Nope. You? Not yet.

Optimists, Damned Optimists & The Deluded

Geo-optimists fall into 2 broad camps -optimists and blind optimists. Members of the first species base their optimism on a certain level of knowledge of their subject; an educated optimism where they believe they have a better than average chance of success given the team’s experience.

The blind optimists are crucial to our poor success rate as explorationists. They’re the geologists who begin to rely on their optimism and very little else. Yes, their read of the geologic evolution of a mineralized system really is better than anyone else’s, and their unique insights will sniff out the big one and make everyone rich. They’re much more dangerous to your investment account because they haven’t a clue what they’re doing, and they don’t realise they’re clueless, but they still believe they’ll succeed at finding a world class mine. (The worst case of this I ever saw was a project in Washington. It sat under a mature cherry orchard and could only be accessed by a hypothetical 13,000 ft long incline, but that’s a story for a different piece.)

The trick to industry survival for both camps is being able to translate that optimism, whatever the flavour, into a pitch that can persuade the money guys that the geologists actually know what they’re talking about.

As Brent Cook will tell you (if you’re able to track him down between pedicures and beach volleyball -oh the joys of semi-retired life) at least two thirds of companies -and hence geologists- are simply trying to up their luck in the discovery game by recycling tired old projects or ideas; optimism based on trying to cut corners. It’s easier than risking everything on the application of actual science. Experience suggests that for these companies luck is still such an important component of the discovery process that very few real discoveries come from their efforts – perhaps 1 in 10 of the good finds that you read about. Brent sees them as basically bullshit plays -a whole leaky raft of explorecos temporarily claiming they’re geniuses, when in fact it was just plain dumb luck that paid for the ski chalet in Whistler.

As an investor, the best time to give any company your hard-earned savings to chase a dream is probably when the optimism has been tempered by gobs of cynicism experience and they’re better able to recognize the fatal flaws, whilst knowing not to give up too easily.

The Majors and Optimism

The major miners (sorry) have a slightly different take on optimism.

Owen, my-ex boss who ran Anglo American’s exploration efforts for a number of years, told me that he’s never subscribed to the need for optimism in exploration and sees little or no room for it. Bear in mind this opinion comes from the big budget camp where it’s perhaps easier to divorce yourself from dreaming of the pot at the end of the rainbow. An $80-million annual exploration budget buys you a lot of chances to get lucky.

Money trees aside, his take is pretty simple. Since the big company needs to find new or replacement resources for reasons of survival or growth, you really only have 3 options. You can buy your way to success, acquiring companies or projects, or you can joint venture into early-stage projects. Alternatively, you can decide as a company to conduct your own exploration. A combination of all of the above is wisest to manage the inherent risks and reduce reliance on optimism. At that point, it’s hello science, and fuck optimism, because who needs it? Exploration becomes a hard-headed game of hiring the best staff; making the best area selection based on the best models and using the best search technology to look for stuff. Good discipline and decision making are vital, and you have to know when to stop if it ain’t working.

Undeterred, I suggested to him that a degree of optimism (and a ton of lick spittle grovelling) was still needed for those vital budget pitches to the Board. To which he replied that the Board simply needed the comfort of knowing that he and his team were efficient managers, not starry-eyed optimists thumb sucking over a map. Hence, he always tried to convey to the executive that 1) the observed geology was compatible with a good model assembled by the best people, and 2) if it looked like a project was a loser, it would be dropped or farmed out as soon as possible before any more money was wasted.

Optimistic Engineering

At the engineering stage, optimism is everywhere. Best project ever! Can’t wait for the PFS results! Cash flow! But engineers are as guilty of blind optimism as geologists. Remember, there’s never been a failed mine without a positive engineering study, right? Consultant engineers are usually a bit more circumspect, presumably because they get sued from time to time when mines go tits up and the raging, red-faced lenders lose their shirts.

It’s a little-known fact (apparently) that 75% of published economic studies will show that their project is in the lowest quartile of operating costs. A fabulous example of optimism, lying or mass delusion, or all 3. Hardly surprising really. Would you want to publish a Friday morning news release showing that your project is going to be one of the highest cost mines in the world? Yes? No? Anyone? But logically, the remaining 25% of projects must be in the er.. upper 3 quartiles. Hmm… 25% = 75%… right, I see. Something’s wrong with this math.

An alternative way of looking at it, quoted to me by another friend (yes I have more than 1) is that only 1 in 20 mining projects exceed the feasibility study forecasts, and 50% do not. One major company found a systematic 4-6% optimistic bias in the internal rate of return for a dozen or so projects it had modelled and built. All of the mines underperformed their cash flow models by roughly that amount. Optimism be damned. The fact is something’s generally wrong with the models. (Hint, the real world is complicated and has a way of messing with engineering assumptions.)

Most investors will only see the inherent engineering optimism at the news release stage: internal rate of return, net present value, capital cost and the discount rate used are pretty much all they ever take on board. The rest is engineering guff but it’s also where the serious optimism comes in to play. Power costs, labour rates, tax rates, grinding indices and a whole lot more – it all flows into an unwieldy spreadsheet model that pukes out the NPV/IRR/Capex summary; numbers we all love and cherish and quote as the sterling silver truth, until the project fails. No optimism here then, move along please…

Ounces Schmounces

The voodoo we call resource estimation takes optimism to a different level and is the cause of many a failed mine. I’ve never tried to fully understand the discipline. To me, statistics is akin to thermodynamics. No matter how many times I sit in a classroom or read Statistics for Dummies, it’s in one ear and rather swiftly out the other, dragging my tiny allocation of math brain cells with it.

If you’ve ever had the misfortune of talking to a resource estimation geologist, it all goes off the rails within 10 seconds of them opening their mouths. I may as well be listening to an evangelical preacher speaking in tongues. It’s like I opened the wrong door and ended up in 4th year statistics crossed with a “How Not To” scientific writing course, taught by a socially maladjusted, beardy, optimistic savant. (Sorry Mike, not you obvs.)

I can grasp averages, medians and the odd standard deviation or two but beyond that I’m useless. I have no choice but to be optimistic and assume that the practitioner of the dark art knows what they’re doing. In fact, I can sum up my understanding of geostats in 2 short sentences: a) when comparing 2 numbers, if their ratio is about 1 that means something possibly important; b) big numbers are generally better than small ones. That’s all you need to know to bluff your optimistic way through a board presentation.

In practice, all of this means that if you give the same set of sample data to 1,000 resource geologists, you’ll get 1,000 different optimistic resource estimates. Management is always convinced that they’ll get the huge tonnages and priapic grades that the investor wants. But to deliver them, the consulting resource person has to dip into an increasingly weird bag of statistical mumbo jumbo. Take Kriging. According to Wikipedia it is:

“Kriging or Gaussian process regression is a method of interpolation for which the interpolated values are modeled by a Gaussian process governed by prior covariances, as opposed to a piecewise-polynomial spline chosen to optimize smoothness of the fitted values.”

Funny enough, one of the quoted disadvantages of Kriging is “Not easy to comprehend”.

By the time all of the optimistic resource cases have been compounded, iterated and checked by the independent peer reviewer, there is absolutely no room for manoeuvre. Iteration becomes a way of life – can we tweak this and try again? We can? Great! By the end, the resource relies on so many convoluted factors; just one has to fail and you’re lumbered with a project that is by now too big to fail or save.

And Finally, Newsletter Writers

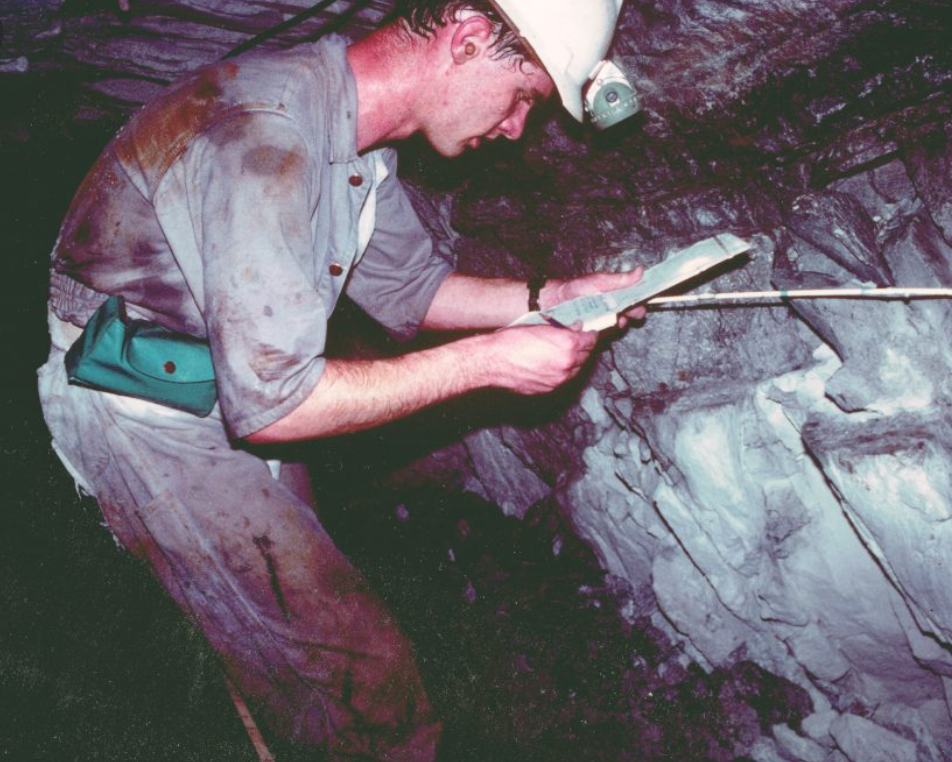

Most newsletter writers are smart, and they’re immensely optimistic most of the time. The latest hot story gets written up in glowing terms, but the rest become yesterday’s news, cast callously aside into the exploreco compost bin with only worms for company. Some writers visit projects. Most will speak to company management at some point, hopefully. And some take nice photos so you can see your company’s team in action. They write thrilling stories about helicopter rides and bears and nuggets and being there to watch as glittery, gold-engorged core slides smugly out of the drill pipes. And then they charge you a fat monthly fee for all that optimism, so little wonder it’s all going to be fine. They want your $500 next year. Yes, you at the back, they’re paid to be optimistic.

Enough Optimism Already

Anyways, that’s a few collected cynical thoughts on optimism in our humble business. You may agree or think I’m completely barking. Whatever. But when you come face to face with it, just remember, somewhere there’s an investor (very probably more than one) who lost their shirt because they blindly trusted an over optimistic team of mining professionals. So be hard nosed. Ask the tough questions, and make sure you peel back the thick, blubbery layer of optimism that we all carry around with us until you get to the real story, warts and all.

What’s your take on optimism? Let me know.

And remember..

If this post didn’t depress the hell out of you, and you’re still hopeful that your mining investments will one day bear fruit and pay for one week of your grandkids’ university ejumakashun plus a nearly-new Toyota Echo for the wife, then please sign up using the eternally hopeful subscription box I placed temptingly at the top of the page. I’ll be sure to send you more misplaced content from time to time. Don’t make me beg…

What a sensational post. I hope you will permit a humble mining engineer to give a small example of his experiences with one of his best mates, Trev. Its a bit of a long story, so be patient until you get to the punch line at the end. This is a story about birds at the end of the day, with a bit of geology tossed in.

Let me start at the beginning. Me, John, and my newly co-minted mining engineer mate Bruce, drove from Sydney to Broken Hill on a Sunday in January 1981 to start our extraordinarily illustrious mining careers. We got there late in the arvo, organised our things in our allocated company quarters and then said “what do we do now?” One of the blokes already ensconced on our quarters said “go to the Pig & Whistle for a beer, its just around the corner.” For someone who was partially raised in a pub, that sounded great advice. So around the corner we go and into the back bar. I can remember this as clear as anything. We got a beer and started talking to a very friendly local bloke; it was Trev. I can remember Trev telling us that the Pig & Whistle was the best pub out of about 40 in Broken Hill because it was the one that all the new female teachers always drank at. And he was there eagerly admiring the new teachers who had also recently arrived. Trev was a few years older than us and he said he was a cadet geologist at the ZC/NBHC Mines, where we would be working the very next day. In those days Broken Hill had a university and the locals would pick a mining course and spend half the week at uni and the other half at the mine. These blokes had the absolute best learning experience. And Trev was the best of the best in the geology facilty. He didn’t need a computer to visualise things; the orebody was all in his head. It didn’t matter which orebody over his career, he carried everything up top. But he did become very computer literate as well, once they were invented.

Over time, the gold boom overtook the shitty base metals business and we all drifted to Western Australia to try our hand at open pit mining. A very funny experience, as none of us had ever seen a real open pit in operation, but we figured if you didn’t need a cap lamp to see things it must be pretty dammed easy. Me, Bruce, Trev and a whole bunch, Terry x 2, other Johns x 2, Phil, all of us deserted Broken Hill for the glamour of the WA gold industry.

After 3 years in WA, eventually my then-wife got a bit lonely and wanted to come back to the east to be nearer her family. Stupid bitch, as I loved working in WA. So she found a job advertised in the small state of Victoria in a gold mine. I got interviewed in Perth and was clearly the only bloke interested in the position as I got offered it. She took a plane and I packed the car up and with the dog we drove across the Nullarbor at the end of 1990 I think. A wonderful 3-day trip; just man and beast and the outback.

I started work and things aren’t quite what I expected. It was a smallish, low grade heap leach operation. Very tough at 0.8 g/t, with a real bastard of a mining contractor. Anyways, it eventually worked out OK. We’d heard stories of another heap leach mine about an hour to the west, so I checked it out one day on a Sunday. Very different to the one I was working at; very different. Eventually we heard this mine had gone bust, despite being owned by a subsidiary of the then-biggest local gold mining company in Australia.

So we talked to the Board and convinced them to let us do due diligence to see if we reckoned we could restart it successfully. We found a lot of problems an our study was fantastic; all the right IRR, etc, so the Board convinced a Macquirie Bank to loan the company AUD$3M to pay the liquidator and take over the property. The first year or so was tough as we worked down through old workings in a few pits, but things turned around, as they often do. By this stage, I was running both the company and the two mines; a wonderful challenge.

Somehow Trev got in touch with me and I told him to get his arse over to Victoria and help me in the new mine. Over he comes, with his lovely wife Wendy and their 2 kids. And Wendy was? Guess it – a school teacher who liked going to the Pig & Whistle. They settle into a nice joint in Bendigo and away goes his brilliant geological mind. I’ve got to say we already had 2 excellent geos, but Trev really filled the team out. Perfect as a mine geo and as an exploration geo as well. The 3 of them dreamed up a geological theory for the deposit. Then in about 1998 we drilled a super deep DDH, all of 300m which was fucking deep back then, to test their theory. Bingo, in the last 50m of the hole we hit the target zone based on the theory, something like 2 g/t over the 50m. Not great, but sure as hell encouraging and the theory was looking good.

Trev had one problem though. He was the eternal pessimist. But because he was such a friendly bloke and a best mate, I’d try and overlook this major geological character flaw. As the years progressed, the gold price was slumping and the ore reserves were running out. We’d have our weekly and monthly management meetings looking for solutions and bloody Trev turned up to each one with his Black Hat (of the 7 hats fame) firmly on his head. Tempers frayed, I’d tell Trev to shut up and take his fucking black hat off. Which he tried to do.

Eventually the shit was really hitting the fan and we needed to raise some money in about 2000 to stay alive. The first time since the bank gave us the original $3M. We’d managed to do amazing things with our high grade 1.1 g/t heap leach mine. Did a lot of drilling, extended resources/reserves from the original 18 months to 10 years and even paid shareholders some dividends. But $250/oz gold was a killer. I asked a fund manager I knew well in Melbourne for some advice. He suggested a few new high profile directors and a good broker to back us. So we took his advice, which sadly entailed appointing a new chairman who was one of the most arrogant, self-centred pricks I’ve ever met. But it worked. With his profile we raised some money and set off on a drilling campaign led by Trev. At this stage we’d already done a pretty good feasibility to extend the mine into what were then refractory sulphides. I drove a programme of met test workusing BIOX, such a great treatment technique. But the new project needed a bit more sex appeal.

So Trev designed a 20-hole exploration programme that was going to discover the mother lode down deep. The broker raised just enough for the 20 holes. The 20 holes were planned and we organised a sweepstakes to see who could pick the hole that was going to hit the mother lode. The holes were drilled, assays received and the largely new board gathered around Trev’s plan table, while he explained that none of the holes had hit anything!!! Nothing, zip, nada. Poor black hat Trev, I’m sure he thought his career was over.

A few days latter Trev came running into my office in a blinding moment of shear optimism ; “John, John, I’ve worked it out. I know why we missed and I know how to find it now.” I said something like “but Trev, we spent all the money, there’s nothing left.” “But I only need one hole, he pleaded, just one.” “But we’ve got no money Trev.” Poor Trev, his one career moment of sheer blind-faith optimism completely exploded in his face.

Next day he came into my office and said “I talked to Wendy last night. I convinced her to let me buy my company car, but only if you use the money so I can drill this ONE LAST HOLE. I’ll find it, I know.” I think by this stage we’d sold off most of the 4WDs, so Trev was left with a very old Australian brand Ford sedan to potter around in. Deal I said. Trev paid the company a couple of thousand dollars and called Frank the driller and told him to be at the mine tomorrow.

Frank drilled the hole, we got the assays back and Trev had found his mother lode; well at least the start of it. “What are we going to call the new discovery Trev, how about Trev’s Lode?” Trev said, no, I think we’ll call it the “Falcon”, after all the model of Trev’s brand-new old Ford was the “Ford Falcon,” a very famous model in Australia.

I said at the start that this was a bird story; so first came the Falcon, then the Eagle, then the Cygnet, the Kestrel, the Phoenix and to top them all off, eventually the most famous of them all, the all-conquering Swan Zone.

And the moral of the story. Nothing about bloody optimism or pessimism, but its to sack any fucking geologist who allows an exploration hole to finish in grade. If we’d pushed on our 300m DDH another 50-100m then maybe, just maybe, we’d have hit the Swan Zone in 1998 and then maybe I wouldn’t be fucking around in a third-world shithole country as I am now now looking for my own Swan.