Regular readers of this blog (both of you) might recall a few stories about my time in western Pakistan in the late 1990s. It was bloody amazing; rough country but an extraordinary experience, except for the nasty gut bug I caught which followed me back to Budapest and then set about exhausting the local toilet paper supply.

Would I go back there? No. It’s even more nuts today than the 1990s and back then it was bloody weird, with drug runners, Taliban incursions, nuclear tests and the odd hotel bombing thrown in for good measure.

I prospected for copper on the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan; the long, straight east-west stretch in northern Balochistan. It’s an arbitrary frontier created in 1893 in the depths of the Great Game between Britain and Russia, pencilled in on a map of the subcontinent by one Sir Henry Mortimer Durand GCMG, KCSI, KCIE, PC.

Sir Mortimer Pencil Line

Sir Mortimer served as the Foreign Secretary of India from 1884 to 1894. He was a stuffy looking British civil servant in the best up-tight Victorian tradition and about as pro-Empire as you could get. His pencil line legacy -originally known as the Durand line- ran for 1,660 miles, cutting through traditional tribal territories and largely ignoring the wishes of the local savages. Its intent was to demarcate the areas of political influence between the British in India and one Abdur Rahman Khan, the Afghan Iron Emir; the man who finally united Afghanistan’s warring tribes. The line still exists although it’s now the modern border between the 2 countries and it still ignores the traditional tribal territories.

For most of its length it’s a bloody miserable place to be. Hot, dusty, mountainous, and as remote a part of the world as you could hope to visit unless you really like rocks and scrawny goats. The stretch I worked – south of Helmand in Afghanistan- was known as “the Wire Road” by the locals; a term I heard over and over as we worked our way north through the Chagai mountain range.

It took me 3 days to get there from the over-crowded hellish sprawl of Karachi. The bumpy flight to Balochistan’s capital city Quetta -with no assigned seating- was complete pandemonium. Then we drove for nearly 3 days on truly shit roads and shittier dirt tracks, with more than our fair share of flat tyres, to the northern side of the Chagai hills (I Met A Drug Smuggler) where our driver finally announced that we’d arrived. Thank fuck, I thought.

Take A Leak.

We were actually on the international border. One side of the road was Pakistan, the other Afghanistan. Impressed with my own daring-do, I did what anyone would do in that situation. I got out of the 4×4, stepped over the line so I could claim to have visited Afghanistan, then I took a giant leak onto Afghan soil -my personal fuck off to the Taliban- and got back in the truck.

Let’s Hear It For Naseem!

Truth be told, I was so far out of my depth culturally that I relied entirely on the advice and connections of an elderly Balochi geological consultant, Naseem, who lived in Quetta. Curiosity got the better of me. Why was it called the wire road, I asked him? Because, said Naseem, there was once a telegraph wire that ran along the road so that the remote British border outposts could communicate with their colonial masters hundreds of long, long miles away to the east, which gave me pause for thought. It had taken me 3 days to get there by so back then it must’ve been one of the most remote corners of the Empire to be posted to. God knows how long it would’ve taken the Royal Camel Corps to get there in 1895.

“Ring Ring”

“Hello? Mumbai? Help, we’re being attacked by hordes of heavily armed tribesmen.”

“Don’t worry, reinforcements are only 17 days away.”

“Ack.”

The Graves

Every 15-20 miles or so along the Wire Road we’d pass a small mud-brick hut with a tin roof, some still occupied by the local Levies men -the armed government border police- but other huts were little more than ruins. It took me a while to figure out that they were roughly one day’s ride apart for a squad of soldiers riding camels.

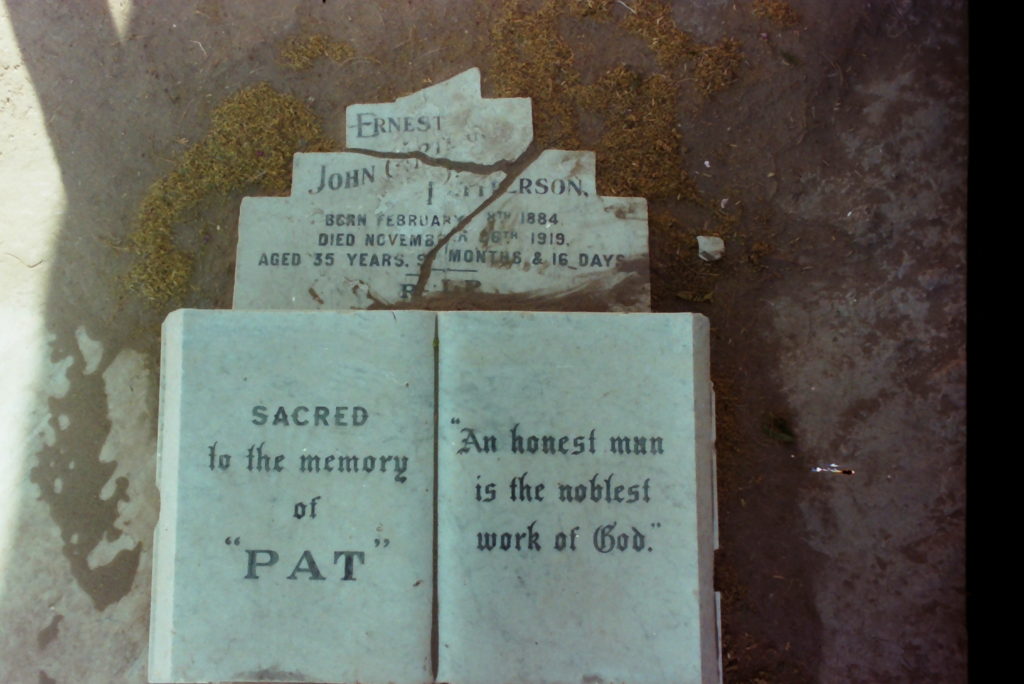

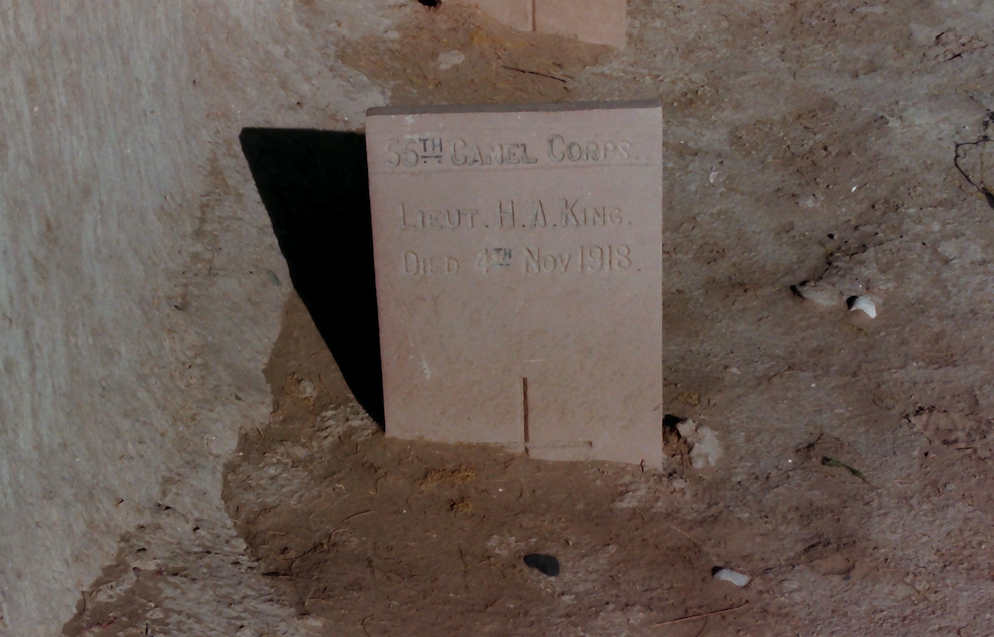

Next to each hut was a small collection of broken or fallen gravestones. The carefully carved inscriptions told many a lonely story. They were all British soldiers, and most had died in their early 20s. They hailed from Liverpool or Newcastle or some other working-class English city, and they’d died from disease (“distemper” “tropical fever”) or they’d lost their lives fighting the local tribesmen to protect the Wire for their Imperial bosses. What they shared was a lonely death thousands of miles away from their parents and friends in England.

A week or so later I was back in “civilization” in Dalbandin, a small, miserable town on the hellish single lane truck road midway between Quetta and the Iranian border. Out for an evening stroll, dodging piles of cow innards and mangy-looking feral dogs, I was stopped on the street by 3 well-groomed, upstanding Pakistani army officers. Shit, I thought. Here we go. They were going to arrest me looking for a bribe over some trumped-up technicality on my visa.

“Do you speak English?” came the question.

“Yes, I’m from there” I replied.

“Follow us.” they ordered.

Yes Sir!

Not being one disobey an armed soldier on their home turf, I did as I was told and followed them back to a well-kept army barracks; all white washed stones and red tiled roofs. The British originally built the base and had stationed soldiers there for decades.

My new buddies took me into a tidy garden behind the officers’ quarters, which was not really what I was expecting. The three of them sat down and politely directed me to sit on a small bench by a picnic table. A command was barked, and a servant ran into the garden from the barracks clutching a shortwave radio that was set down on the table between us. It was tuned to the BBC world service, broadcasting the Pakistan vs England test match from Lord’s cricket ground in London. The servant -known as a chaiwala– brought us fresh rose water and pastries, and as we sipped we listened to the soothing sounds of leather on willow and the soporific BBC cricket commentary until the close of morning play.

Around the base, heavy trucks threw up clouds of dust as they plied the truck road through Dalbandin, and the call to prayer from the local mosque eventually muscled into the radio commentary for a minute or two. Despite England being in control of the game, which was a source of huge anguish to the officers (cricket is life in Pakistan and India), the three of them were very magnanimous company although I failed them miserably when they tried to talk cricket with me. I had no bloody idea who was on the teams – a shocking state of affairs for an English man apparently.

More Graves

After tea, they took me to see a small, well-maintained graveyard behind the barracks which held more British soldiers’ graves. The senior officer explained that they made sure the plot was looked after, and every so often fresh flowers would be placed on the graves. They specifically wanted me to let the British government know that the remains of their fallen men were being taken care of. They had no contacts to approach in the UK and hadn’t had a Brit visit for years, so it fell to me to report back. They’d looked after me so well that afternoon that I couldn’t say no and when I got home, I did as they asked.

The Commission

I took lots of photographs of the graves, partly for my own historic interest, and partly to document their condition. There’s an organization called the Commonwealth War Graves Commission that records and maintains (where possible) the graves of soldiers who fought and died for the what was then the Empire. When I got home, I wrote them a polite letter and tucked copies of all of my photos with their locations into a big brown envelope and mailed it off to their offices in Maidenhead.

A few months later I received a reply from a nice woman at the Commission. She told me that they had historical records of the graves I’d seen, but nobody had reported on their condition for close to 50 years. I was the first Brit to have seen them in many decades. They thanked me profusely for writing to them and said they’d be asking the Pakistan government to right the fallen stones if possible.

Funny enough, I actually believed that the Pakistani authorities would do it; or at least their officers in Dalbandin would if they were asked to. Despite Britain’s colonial history, many of the country’s army officers were (are?) trained at Sandhurst military college in England. They had a strong sense of respect for all military war dead and a strange nostalgia for the structure and bureaucracy of the Empire days that confused the hell out of me and didn’t mesh with the deeply negative post-colonial newspaper narrative in the UK. Nostalgia wasn’t part of the story.

A Quick PS:

Seeing the graves brought back the words written by Rupert Brooke in his poem The Soldier, penned before his untimely death in the trenches of World War 1 in 1915. It’s of a time perhaps, but still movingly evocative of the loneliness of a foreign grave.

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware,

Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam;

A body of England’s, breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.

And remember..

Please subscribe if you liked this piece, using the subscription box at the top of the page.

Beautiful Ralph. Your blog is a cut above the rest. Please keep it up.

thanks Tim. Truth is stranger than fiction right? All of us field geo have stories – we simply have to persuade each other tow rite them down!

Great story Ralph….love reading about your adventures as an Explorationist! Keep them coming….

Cheers, danièle

many thanks Daniele!

Ralph, I am a geologist from Chagi(my village is close to the Afghan border), but I never knew about these graves. I have read most of your blogs and your writing gave me the incentive to write a blog which I did so. Have you worked in the Reko diq area ?

Must be appreciated it.

Hi Shahzaib, I passed through the Reko Diq area but never visited the project. Ralph

Ralph, were you working for any company when you visited the area? Firstly, I thought you may have worked in BHP, but after reading a few of your other blogs, I came across you were with the Anglo-American company, not BHP.

Thanks

yes, I worked for Anglo American, in Pakistan and in Iran.

Then why didn’t any discovery (ore body) made? in-particular Pakistan

Thanks for yet another interesting blog. I enjoy them all! I suppose we are lucky that we are geologists with many stories to tell. My kids just want to be perpetually looking down at their phones (brain drains I call them!) while I am out and about living. Their world is looking down at a few square inches of LED phone screen, while mine is looking up at the fresh air, sunshine and real live people. Oh how things have changed (for the worse?). Thanks again.

Ralph…. beautiful piece…. you are lucky (I guess) in that your work took you to places very (very) few would otherwise go. Equally lucky to have survived.

I came close a couple of times!

Hi Ralph, greetings from Jakarta, great post above. i came across similar vintage graves of Australian soldiers in a small cemetery outside ting place called Ottoshoop, near Mafeking, close to Botswana-South Africa border. Possibly from the Boer War . Rgds, Steve

It shouldn’t have surprised me bearing in mind where I was working but it did.. I was very moved to see the headstones and it was easy tom imagine the sound of scouse and cockney voices 100 years before.