Some people are accident prone. It’s a fact. They have a higher predisposition to kitchen injuries, car crashes and the like and it’s a bloody miracle that some of them make it through adolescence without limb loss.

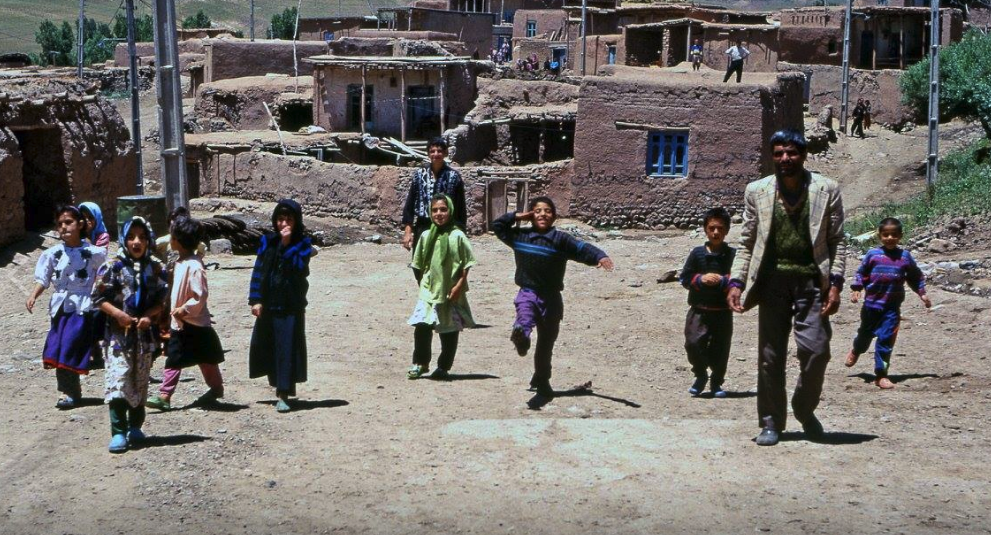

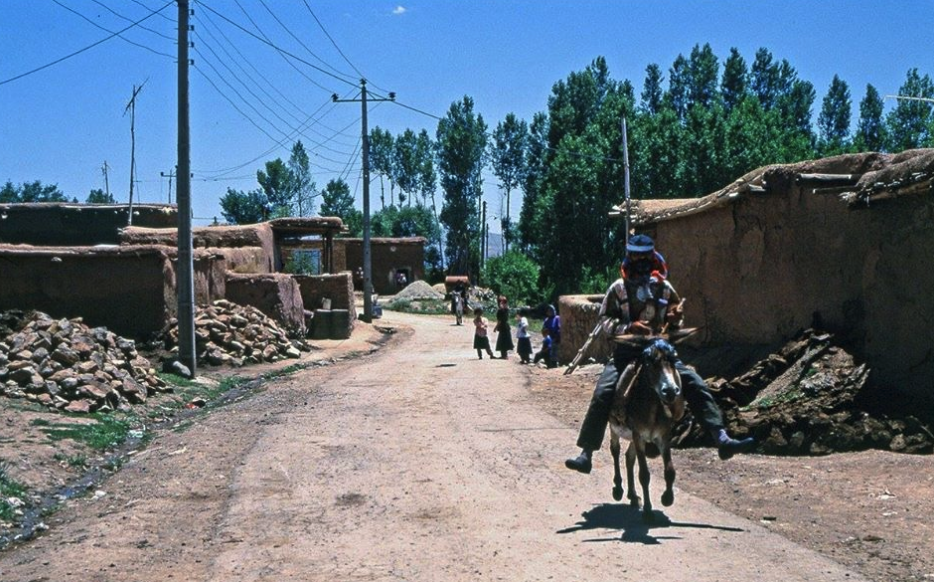

I had a field assistant once who suffered more accidents in a short period of time than anyone I’ve ever met. His name is Nejav and he lives in a small village in north-central Iran. My western geo-colleagues nicknamed him Yes-Yes because that’s all the English he knew.

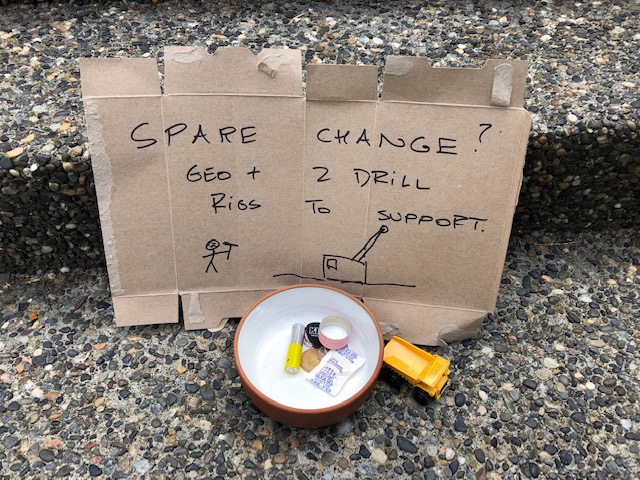

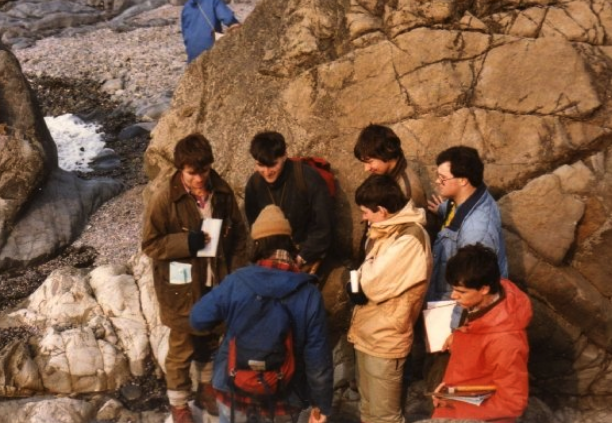

Yes-Yes was/is a funny man. Happy as a clam at high tide, he cheerfully carried my backpack and rock hammer as we tramped across thousands of square kilometres taking stream sediment samples and prospecting for mineral deposits. He was with me when I went through my tortoise-signing phase and later on, he trained as a drill offsider to work on the drill rigs as we poked the first holes into the Zarshuran gold project.

Continue reading “Accidents Will Happen”