i·so·la·tion

/ˌīsəˈlāSHən/

noun: 1. “the isolation of geologists”

We’re Lonely Bastards

Every geologist has experienced extreme isolation at some point; a moment when they realise that if anything bad happens to them right then and there, they’re screwed. They may as well be on Mars because no help is coming. For most geos, isolation is a regular Saturday night thing when our one “friend” -the one that stills listens to our no-please-not-again hilarious field stories -is unexpectedly busy taking care of their incontinent senile aunt. Would you believe it? I’d love to meet up, but I have to change Auntie Mabel’s diaper. Gosh is that the time…bye…

Yobs

Soccer fans -like my mate Neil- often experience isolation at away games when they accidentally stray into the local Ultras’ bar and come face to face with 65 drunken lunatics sporting matching death head tattoos. I’ve been there. Forty years ago (gulp) on a field trip to Dorset me and 2 fellow geology students were the target of a gang of skinheads in a pub itching for a kicking; but I digress, that’s not where I’m going with this story. I was curious about the concept of loneliness and separation so I polled some industry friends of mine for their recollections of those peculiar flashes of intense isolation. Here are a few of their stories; a big thanks to everyone who told me a tale.

Enough Of Yobs

Trudging around the Beaver Creek mining conference last week heading for my 20th meeting I ran into my friend Andrew who I’ve known since (ahem…) my South African days in the mid-80s. Andy’s career took a different path to mine he was fairly successful and he ended up manager of a medium-sized gold mine in northern Canada. His loneliest moment was stepping off the flight to the mine for the first time in his capacity as mine manager. He knew that there was nowhere for him to hide if he screwed up. No boss to hide behind or colleague to blame. It was his neck on the chopping block.

Down Under With Mark

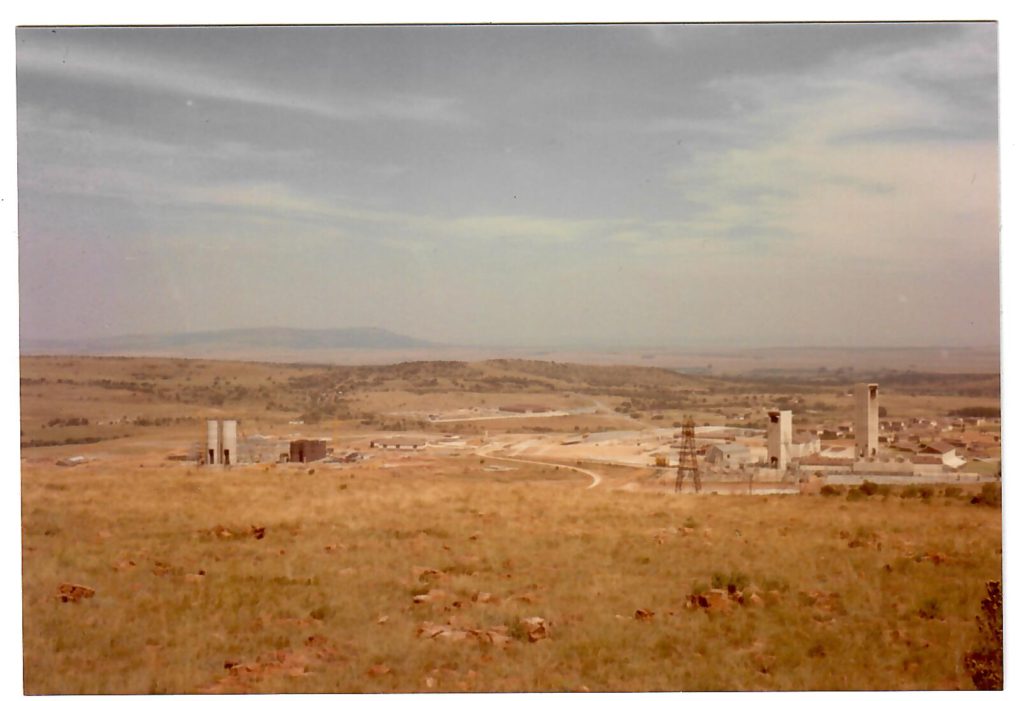

My friend Mark G had a different mining experience. He and I both worked on the same South African gold mine in the 1980s. I didn’t know Mark at the time but we knew (know) some of the same people and had many similar experiences during our time underground. Mark’s well travelled; a globe-trotting man-of-the-world geologist with multiple projects under his management – a true James Bond of mineral exploration but not as boozy. Or well dressed. Or casually violent. So, not like James Bond at all really but he has been to all sorts of exotic places for work.

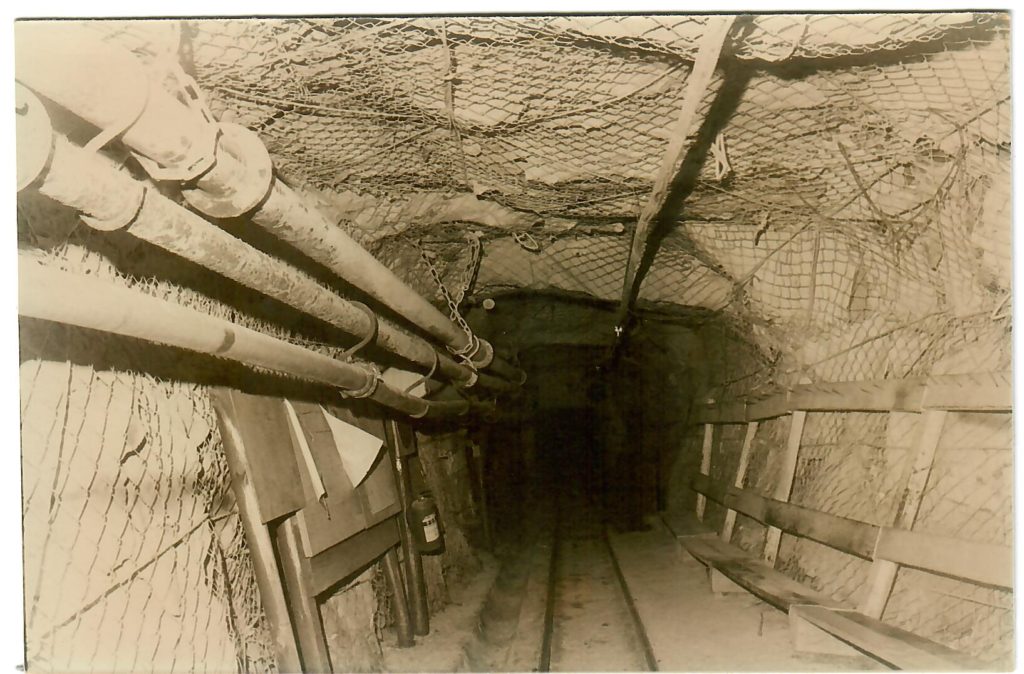

He flagged a moment in his mine geology career when he was mapping an unventilated tunnel face 6,000 feet down at Vaal Reefs 8 shaft. At those depths unvented tunnels can get very hot very quickly and you don’t stay there long because heat stroke can hit hard and fast. He remembers he was wearing an ice jacket; a jacket lined with pockets that hold blocks of dry ice which is supposed to allow the wearer to take the heat for longer.

Despite the ice jacket he was starting to suffer from some heat-induced confusion and, in a daze, decided to switch off his head lamp. He was immediately plunged into complete and profound darkness, like being on the bottom of a deep ocean. He could hear the rock face cracking and popping as the ambient rock pressure unloaded into the newly created tunnel space. The distant sound of drilling in an adjacent tunnel sounded like the engine of a passing boat. I did the same once in an empty cross cut -no drilling or rock cracking to intrude on the stillness. It’s a very spooky experience which is hard to replicate at surface.

It’s Rory’s Turn

Another friend’s story had a geographic slant. Rory was working on Victoria Island in the Northwest territories, as close to the middle of nowhere as you could hope to find. His crew were exploring for nickel, copper and PGE metals for a South African client. He had, in his own words, limited Arctic field experience; not ideal as he stepped out of the chopper in early April some 150km from the nearest settlement. It took 3 attempts for the pilot to get the crew of 15 into the camp at Holman Inlet which was a cluster of frame tents next to a small lake that doubled as a year-round runway.

It’s a classical Canadian field camp story. For 6 long weeks he was trapped in a “camp full of nutters”, visited from time to time by assorted itinerant wildlife, some of which was dangerous (wolves, bears) and some edible (caribou). The camp cook was a bible-thumping Lutheran creationist who would ask grand and elaborate questions about big geology; topics like plate tectonics or radiometric age-dating. Rory would explain each big idea to him, and then the cook would blandly state that it was all nonsense because it was all created by God, before serving the left-overs soup. It was extreme social and geographic isolation, and the barren landscape only served to remind him that he was a million miles from his base in Toronto. The only thread of sanity left to cling on to was their work which was moderately successful. They found semi-massive pyrrhotite with neat little wisps of pentlandite that assayed up to 6% nickel and the project was eventually sold to a Russian group.

And Now Over To Steve.

Steve S., a fellow Brit with an identical earth science education to me (Portsmouth in the UK, then the U of Alberta for an MSc) had his dose of extreme isolation when he was prospecting in northwestern Greenland for Rio Tinto in the early 90s. He and another geo were helicopter prospecting an area north of the American airbase at Thule; an area so isolated and lacking in tasty game that even the Inuit avoided it. It was basically an Arctic desert. This was well before the coming of GPS when geologists still knew how to read topo maps to find their way around, although Steve’s maps turned out to be incorrect; in many places there was land where the maps said ice and vice versa.

He was dropped off each day by chopper, accompanied by enough supplies and camping gear to survive for a week if the chopper couldn’t get back for any reason. His boss would accompany him dressed in a nice pair of brogues, carrying a small game fishing bag over his shoulder (hopefully containing a bag of crisps, a scotch egg and a can of Tizer.) They were packing a shotgun and solid lead slugs to shoot any overly curious Polar bears, but luckily never had to test the theory that the pop gun would protect them from becoming lunch.

Greetings From Pakistan

My own oh fuck moment came during a prospecting trip to Pakistan which I’ve written about before on this blog. After hunting porphyries around the giant Reko Diq project, me and my small crew headed west to Taftan -out where Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan meet. From there we headed up to the copper mine at Fort Saindak where we spent a night. The next day we headed further northwest up to the pointy bit of western Pakistan where it says Maki on the map. Believe me when I tell you there’s nothing there, just small dusty rocks and bigger dusty rocks and a few nomads tending wiry goats.

We did our job and prospected for a day; there was some evidence of alteration, possibly some VMS style mineralization, but aside from that nothing. That evening, our choice was to sleep in the trucks or drive through the night, which was risky because the area was infested with drug smugglers hauling opiates through from Afghanistan. So, I was very relieved when we came across a small group of locals busily preparing their evening meal of goat and roti by an orange campfire ringed by traditional black, peaked tents. We parked up and introduced ourselves. Then we did what we always did and bought a goat for dinner. We’d get the choice cuts of meat, and they’d get the rest of the carcass PLUS the $15 payment for the goat to boot. They kindly cleared out a tent for us to sleep in; an open sided one which allowed a through breeze, and as the sun set over the rocky wasteland of southern Afghanistan, we bedded down on coarse wool carpets, large scratchy pillows, our bellies full of goat curry.

Tenty Goats

The next morning, I woke up completely disoriented. Opening my eyes, I couldn’t remember where the hell I was. The first thing I saw was a black tent over me, with 7 or 8 young goats clambering on the roof. Two more goats, braver than the others, had come into the tent and were eyeing me warily from across the scabby carpet floor. Then it hit me. I was 3 days east of Quetta, the capital of Baluchistan along a wretchedly bad road. If I went west, I’d have to travel through Iran to Tehran; a 3-day drive even if I could get across the border without a visa. My third option was Afghanistan (ha ha ha etc.). I had no way of contacting my family or the office in London. The nearest telephone was fifty miles away in a grubby post office, and I was totally reliant on Naseem, my Baluchi guide, to talk to the locals who I hoped weren’t affiliated with the Taliban. It was a worrying moment of clarity.

Thankfully, I was at the end of my trip. That day we turned around and headed back along the anarchic N40 highway to the the Quetta Serena hotel, a small oasis of local sanity, a few days away. When I checked in, I got the welcome news that my apartment in Budapest had been broken into and a bunch of stuff stolen but there was bugger all I could do about it.

Do you have a tale to tell? That squeaky bum moment when your world began to contract around you with no obvious way out? Leave a comment.

And remember…

I’m a lonely chap. Blogging away here in a feedback vacuum. Please help me overcome my extreme social isolation by subscribing for my sporadic articles via the welcoming, uber-social subscription box at the top of this page.

My first job after graduation was as a geologist on the Zambian Copperbelt (there were only two jobs on offer and as I didn’t fancy mud-logging in the middle of the North Sea I headed for Nchanga

When my 3 year contract was finished I had a quick trip flying from Lusaka to South Africa to visit friends

On my return there were no flights back to the Copperbelt from Lusaka so I headed down to the bus station to catch a bus back to Nchanga (a 4hr journey)

This was at the height of the guerilla war between Ian Smith’s Rhodesia and the ZANU/ZAPU fighters based in various camps in Zambia

I got on the bus on an empty seat and a drunken soldier carrying a rifle decided to sit next to me (obviously curious why a white man would be traveling on an old rickety bus)

He then proceeded to interrogate me as to why I was on the bus, I feigned sleeping by banging my head against the bus window but he nudged me and demanded to see my passport

I was born in Bulawayo, and this fact was clearly stated in my passport i.e. I was a white Rhodesian traveling on a bus in Zambia going past various guerrilla camps full of gun toting terrorists. My “friend” with the gun started working his way through my passport and I realised it was only a matter of time before he got to the page stating that I was born in Rhodesia and would then haul me of the bus and shoot me for being a spy (as had happened to quite a few white people in Southern Zambia at the time)

He got to the last page of my passport and turned it round 180 degrees to look at my photo and I realised that he was illiterate and that I was safe

I have been a big fan of illiteracy ever since . . .

LOL. thanks Micky … once drove that road from Vic Falls to Bulawayo when it wasn’t advisable to stop anywhere along the way. Focuses the mind when you’re redlining the petrol tank with 50km to go.