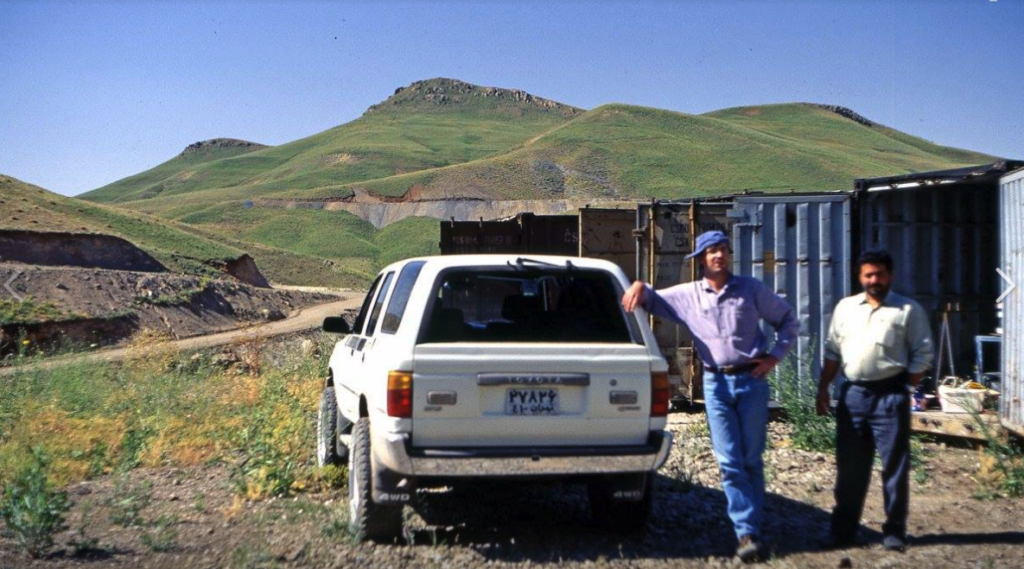

My Iranian sojourn in the mid-1990s has become a rich source of travel stories for me. I spent the best part of a year in the country, over about a 3-year period, travelling extensively in the north, based in the small farming hub of Takab in West Azerbaijan province, 5-6 hours drive northwest of Tehran. The people of Takab are Turkic and Kurdish. The Kurds are easy people to spot, dressing far more colourfully than the Turkic or Persian people. There is also a small minority of Zoroastrians, one of the oldest known religions, who worship at fire temples and sometimes still leave the bodies of their dead in high places for scavenging birds to eat.

Takab’s main claim to fame is that it’s the jumping off point to visit the nearby ancient ruins at Takht-e-Soleyman, now a Unesco World Heritage site. It’s also a trading centre for carpets made by the nomadic Afshar tribes. My driver, Aslan, would happily regale any foreigner he came across with his one and only English phrase: “Takab is a famous town where they make Afshar carpets.” which actually came out as a single word, prompting puzzled stares from the tourists he inflicted it on.

“Takabfamesforafsharcarpetmanymadehere.”

I digress.

Everyone in Takab knew about me, the tall, western engineer from “Inglistan” who was building the gold mine 45 minutes up the road at Zarshuran village. Foreign tourists passed through in buses fairly regularly on their way to the Unesco site, but I was there for 6-7 weeks at a time and became a local fixture. I was once invited to be guest of honour at a Kurdish wedding near the hotel –it was segregated into separate rooms for men and women- and remember the women coming in to the room where the men were seated, to look at me, the ferengi (foreigner). They watched, fascinated, as I tried to follow a traditional Kurdish wedding dance with their men folk.

I worked closely with Yasar, a Turkish colleague. Yasar has an easy going manner, and was well-liked by the locals who considered him one of theirs. We always stayed in the Hotel Ranji, a bit of a shit-hole to be honest, but by far the most comfortable place in Takab. The eponymous owner, Mr. Ranji, was a part-time justice of the peace, charged with overseeing minor court cases and destroying contraband, mainly smuggled booze. Yasar and I spent countless hours sitting in the tiny lobby of the hotel watching local soccer games or cooking shows on the ratty old TV, while the good people of Takab passed by outside.

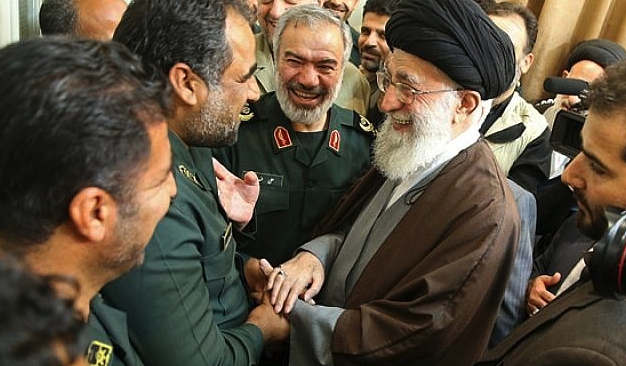

Our sleepy field life changed one day when a federal circuit judge showed up at the hotel. He planned on staying for a week or so to take local criminal cases at Takab’s court house. A devout Muslim, he was also a committed pro-regime official who believed 110% in the divine mission of the Iranian Revolution. He quickly got to like Yasar, and regularly tried to persuade him (a secular Muslim) to go to the Mosque to pray. He spent hours spouting revolutionary dogma, hoping to convert Yasar to the cause. Moreover, he was openly dismissive of me, the Satanic westerner, and wouldn’t talk directly to me, so we quickly reached a state of silent, stand-offish tolerance.

“I know, non-stop laughs.”

One evening, towards the end of the judge’s week in residence, Yasar came to me in a panic begging to be sent back to Tehran the next day. Something had happened between him and the judge; it was rare to see Yasar so flustered, so this was obviously a crisis we had to deal with fast.

It was worse than I thought. The Judge had invited him to be the guest of honour at a special event the following evening. Every night he’d been telling Yasar about the cases he was hearing, giving him progress updates. The day before, he’d condemned two men to death for murder. All good and well, until he told Yasar that they were going to be hung in the school playground behind the hotel the following day, and invited him to be the guest of honour. He was cordially requested to sit next to the judge, on a white plastic chair, centre stage sipping sweet, black tea, while the condemned men were strung up by mobile crane and left to dangle. Curiously, my colleague wasn’t so keen on having to watch all the twitching and gasping, while making small talk with the collected officialdom of Takab.

The only phone we had access to was in the lobby of the hotel. I quietly asked Mr. Ranji to let me call our representative office Tehran for a quick word with our man in Tehran. After a brief discussion, it was agreed that the Tehran office would call the hotel with news of an urgent family matter that needed Yasar’s immediate attention, summoning him home. The call duly came, and we quickly packed him into a car and sent him north to the city of Urmia near the Turkish border. He was under orders to wait there in a hotel until we gave the all clear that the hanging was done and judge had left.

I buggered off into the field early the next day, and came back very late when the fun was over. My tiny hotel room window, such as it was, overlooked the school field where the 2 mobile cranes were already parked, sporting two hefty looking hooks, and I had no desire to be press ganged into witnessing revolutionary justice first-hand.